Four museums that chart Qatar’s ongoing transition from a sleepy pearl-diving town to an emerging world city are now fully open to the public.

The restored heritage houses are in the heart of the Msheireb Downtown project, and capture the massive changes Qatar has gone through in the last century.

They delve on topics like slavery, domestic living and the grueling labor of Qataris in the very early days of the oil industry in 1939.

Originally scheduled to open in December 2013, the museums project hit a number of setbacks, including a fire. It soft-launched last October, although only for pre-arranged group tours.

Here are some key things to look for when you visit:

History of slavery

One of the highlights of the museum complex is Bin Jelmood House, which examines the history of slavery in the world, the Indian Ocean region and specifically in Qatar.

At the entrance of the renovated former home of the renowned trader Mohammed “Jelmood,” who lived there in the mid-20th Century, states the purpose of the museum:

“Bin Jelmood house exists to promote reflection and conversation on important truths about historical slavery in Qatar and the critical issue of contemporary slavery around the world.”

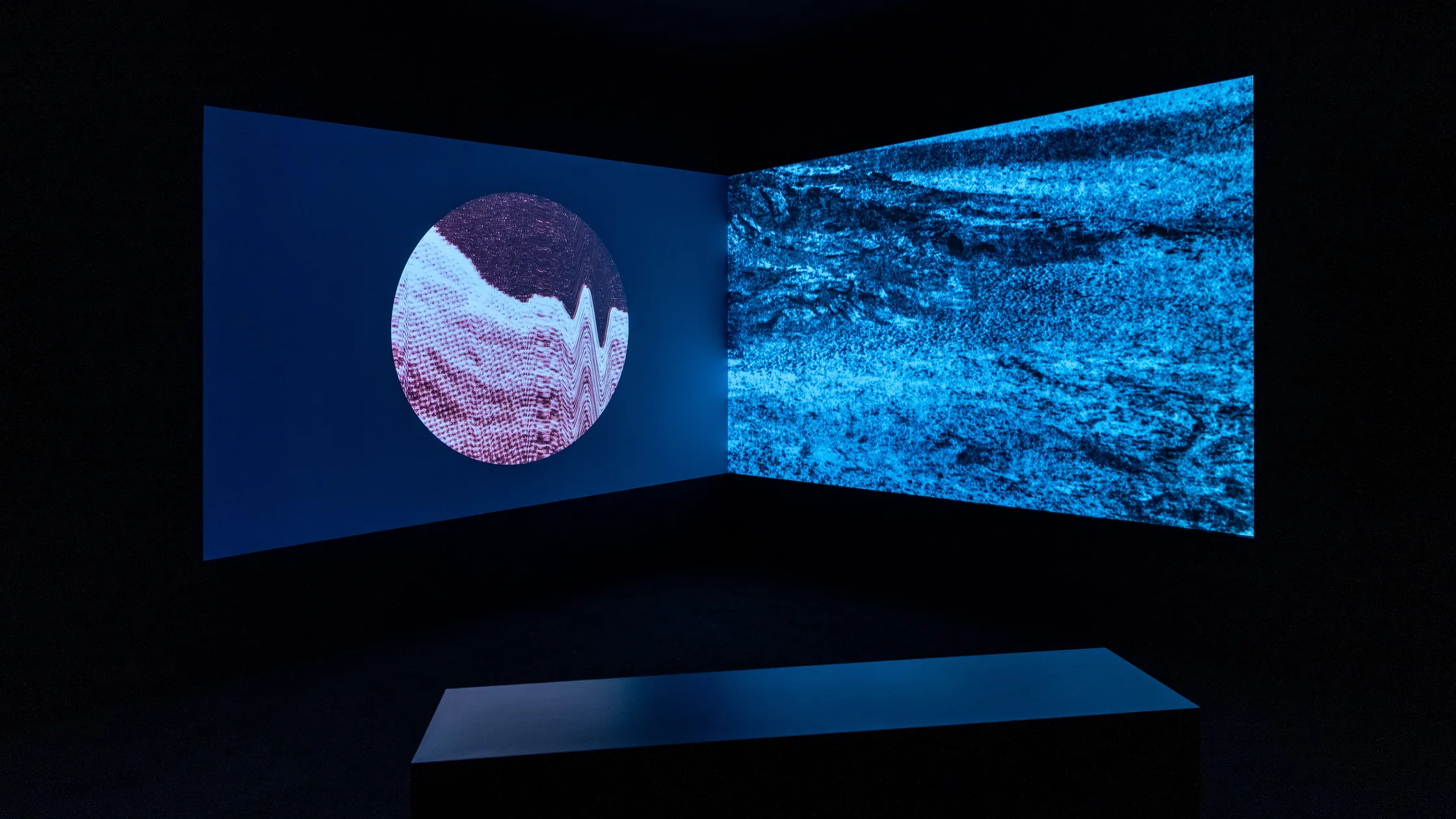

Inside, powerful audio-visual displays recount how a slave would have felt, being taken from their home country and brought across the sea, or by land, to Qatar in the past.

Exhibits also describe how men and women, mostly from East Africa, were expected to adapt to what was harsh and basic living conditions. Many worked as domestic staff or in the pearling industry as divers.

“They might have sold my body, but my soul they can’t claim,” one of the first-person accounts say.

The final section of the museum examines modern manifestations of slavery globally, as well as at home.

One display board for contractual enslavement features a photograph of construction workers in Doha.

It also shows some ways Qatar has aimed to combat people trafficking and slavery, including outlawing child camel jockeys in 2005 and establishing a safe-house and rehabilitative center for trafficked women.

Domestic life

Radwani House is a restored former home that shows what domestic life would have been like for a relatively well-off Qatari family through the decades.

The courtyard house was originally built in the 1920s, then bought by Ali Akbar Radwani in 1936. It sits between two of Doha’s oldest districts of Mushereib and Al-Jasrah.

Radwani’s family left the home in 1971 and it lay derelict for decades until the Private Engineering Office (PEO) took it over in 2007 and began restoration work.

Situated around an open-air quadrangle, one wing examines the archeological work that went on underneath the house.

Experts from University College London Qatar excavated the ground between 2012 and 2013 and uncovered an old well and one of the walls of the original house.

Some of the artifacts they found gives an interesting insight into domestic life then, including a 1920s coffee cup which would have been used for drinking tea.

Meanwhile, a limestone incense burner from the 1920s or 30s was uncovered, still containing ash from when it was last used.

Visitors can also tour round replica bedrooms, a kitchen and majlis, which takes them from the 1950s to modern-day.

Pioneering workers

Company House is the former headquarters of Qatar’s first oil company.

It features numerous first-hand accounts of the grueling life endured by Qatari workers in the very early days of the oil industry.

The entrance has six life-size, white models showing the different jobs these men did during the middle of the 20th Century.

Interactive information tables include snippets of comments. One by Ibrahim Matar Al-Mohannadi stated:

“We lived in sort of barracks made of wood. We laborers lived 20 to a room and we slept in beds made of iron. Drivers were sometimes four to a room and had their own cook.”

There are also excerpts from the memoirs of the British company clerk Robert E. Hill, who came to Qatar in 1948 and worked there until 1955.

He describes first-hand how he traveled to Doha by sea from Bahrain, sharing his thoughts during the six-hour dhow trip, surrounded by food and provisions for the pioneer oil workers.

One section of the museum gives profiles of eight Qatari men who worked with the company, where terrible food nearly caused them to go on strike.

Many were injured in the perilous work and were made redundant from the company.

Hussein Bin Hussein Jaber, known as Bu Abbas, became one of the best-known employees of the firm. Despite injuries, the trained oarsman, who became a company driver, returned to his roots and bought 14 boats which he moored off Doha.

Getting electricity

The final building, Mohammed bin Jassim House, is near the mosque and Eid prayer ground. It was built by Sheikh Mohammed bin Jassim Al Thani – the son of the founder of modern Qatar.

Visitors here get a sense of the impact the sudden oil wealth had on everyday living in Qatar.

Life-size video screens feature Qataris talking about the importance of Kahraba Street in Musheireb. The commercial hub of the area, it was the first street to get electricity in Qatar.

The arrival of cars, air-conditioning and cement transformed the old Musheireb area. Many of these changes also transformed the architecture of the district.

It also gives a sense of the sudden, initial population explosion. Doha quadrupled in size, from just 20,000 people in 1951 to 80,000 in 1975.

Then, as now, the city adapted, expanded and continued its development.

Msheireb Museums are behind the National Archives, on the corner of Al Rayyan Road and Al Asmakh Street.

They are closed Sundays and open Monday to Thursday from 9am until 5pm. On Fridays, they’re open from 3pm until 9pm, and Saturdays from 9am until 9pm. Admission is free. A map showing nearby parking is here.

Thoughts?