A group of three 1,000-year-old Quran vellum folios with Kufic and New Scripts will soon be put on sale in London.

The 9th and 10th century parchment pages included in the Chiswick Auctions sale of Islamic and Indian art on October 28 date from the early years of Islam.

Together they show the evolution of calligraphy from the mature Kufic Abbasid style to the hybrid form of the so-called New Script, laying the ground for the development of the modern script in use today.

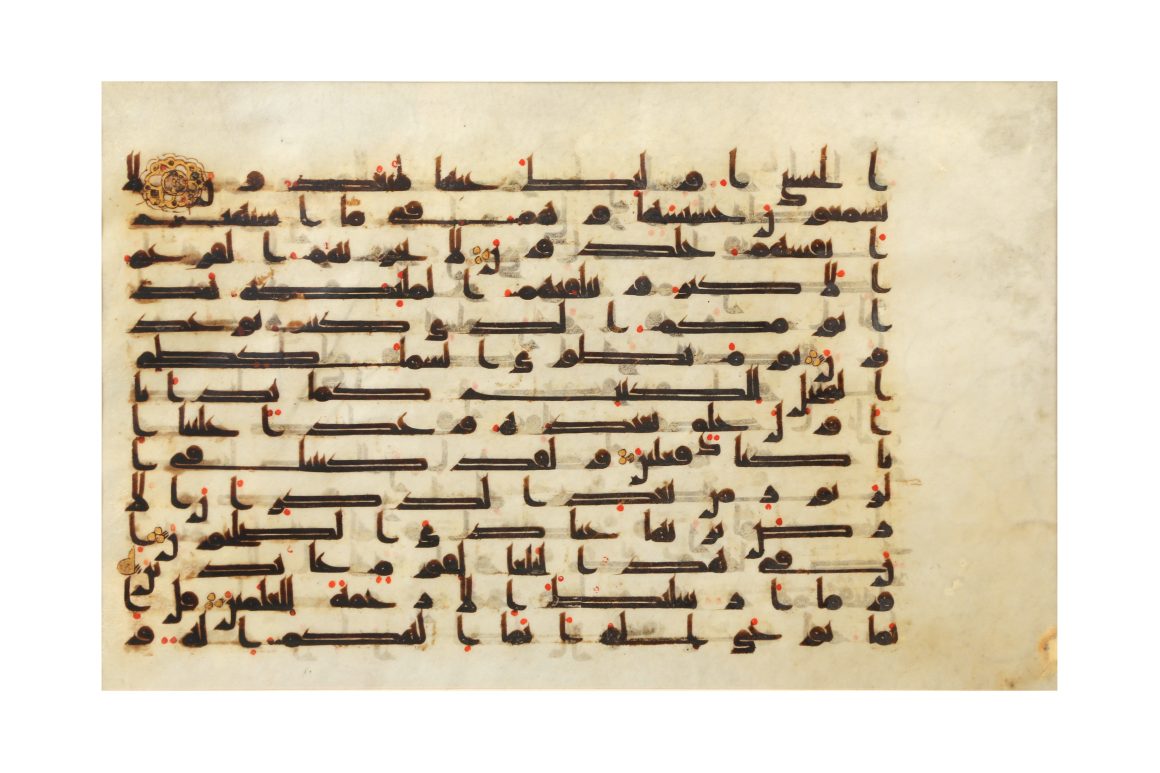

Parchment folios would have most likely been once part of small multi-volume Qurans, which were very popular in the 9th and 10th centuries. Their style tended to be strikingly simple with each folio containing just a few lines of text.

The focus was simply on the written word and the austerity and beauty of the Kufic script itself, with discreet verse markers in green or gold and red dots for the vocalisation the only embellishment.

The earliest folio in the group is from a manuscript on vellum written in North Africa or the Western Islamic world as early as the 9th century. The Kufic text, six lines from the Sura al-Anbiya, stands out for its elegant use of mashq or keshide (extensions of the horizontal letters) that is used for aesthetic effect.

It has an estimate of £5,000-7,000.

A late 9th – early 10th century Kufic Quran folio from the Near East or North Africa displays lines of the mature Abbasid style of Kufic script (estimate £800 – £1,200) while a 10th century folio displays a hybrid script, with more angular contours associated with the so-called New Style scripts (estimate £2000-3000).

The New Style was product of a compromise between the art of calligraphy and every day writing practice.

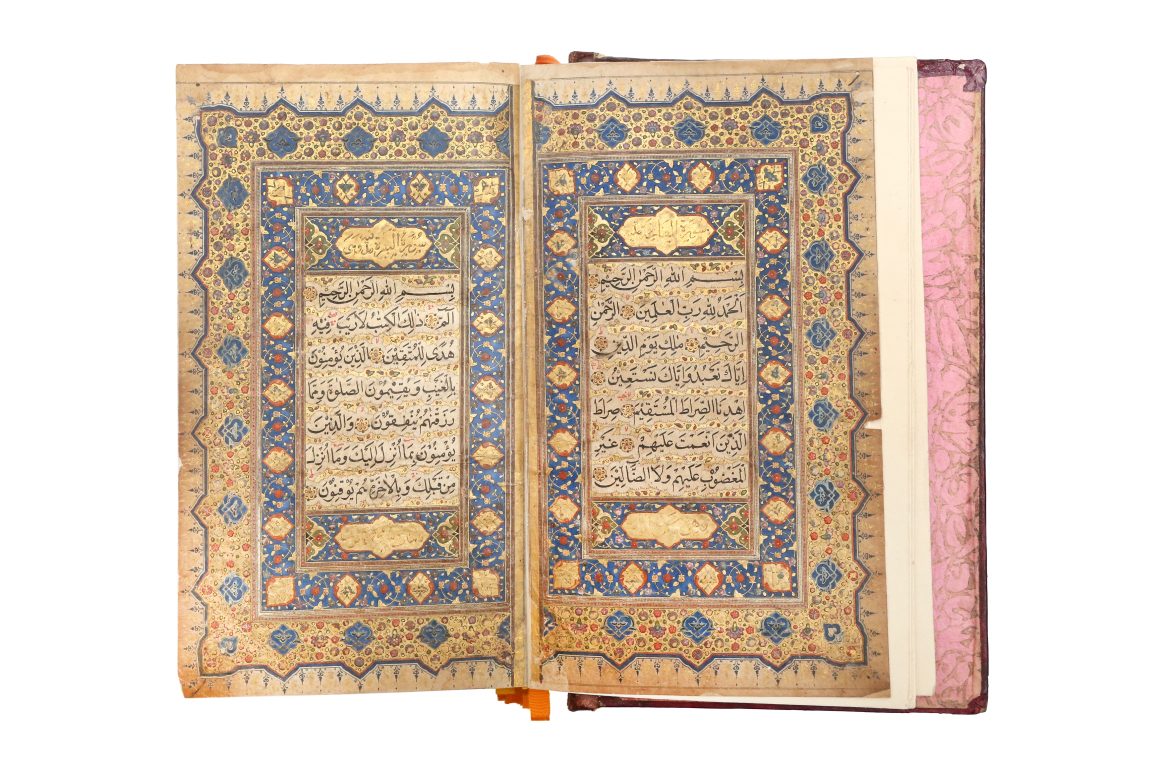

Another lot set to be exhibited at the Chiswick Auctions Islamic Art sale is the fine Indian Quran from the second quarter of the 18th century, guided at £6000-8000 with a 2017 Christie’s provenance.

Possibly made in Golconda or Hyderabad, it is penned in a crisp black ink naskh script (the favourite of the sixth Mughal emperor Aurangzeb) and elegantly illuminated with dense floral decoration in gold and polychrome.

The colophon is signed Ahmad bin Mulla Uthman and dated 1145 AH (1732).

18th-century Indian Qurans are rare to come by, since the patronage of such manuscripts was a low priority for early Mughal rulers. However, under Aurangzeb’s reign (1658 – 1707) and his successors, a new legacy and interest emerged, and religious manuscripts produced around this time represent the first true moment of glory of Indian Quranic material through eminent royal commissions and stylistic standardisation.

Another star lot in the auction is a pair of Indian gem-encrusted gold and champlevé enamel arm bracelets (bazubands), expected to bring £5,000-7,000.

The nine gemstones are ruby, pearl, coral, garnet, blue sapphire, cat’s eye, yellow topaz, emerald, and diamond – the so-called navratna gems that represent the nine celestial bodies of Hindu astrology.

Carefully arranged to follow cosmological rules, each panel is centred by a ruby – the gem of the solar deity Surya. A favourite adornment of the Mughal court, this pair were made in Jaipur in the first half of the 19th century.

Among the Indian miniatures is an illustration from Rasika Priya, the epic story of love, longing and regret, painted in Mandi c.1810. The scene of Radha and Krishna on a moonlit terrace is attributable to the influential Guler court painter Sajnu who revolutionised the pictorial style and vocabulary of the small Mandi atelier when he found work in the Himachal Pradesh province.

This illustration, purchased from the private collection of Francisco Garcia in New York, comes for sale from an American collection with a guide of £4,000-6,000.

A single owner collection focusing on the arts of Iran is offered in the morning session. Some fine pieces of metalwork are led by a 9in (22cm) incense burner in the form of a lion made in eastern Iran or Afghanistan in the 11th or 12th century. Such zoomorphic openwork bronze incense burners are perhaps the best-known metalwork creations of the Seljuk period in Iran.

Felines appear to have been the most popular subjects, but birds of prey were also common. The head and neck of this example are a later addition while the floriated tail shows areas of resoldering and may be a replacement – hence the accessible guide of £3000-5000.

The importance of the written word in Islamic culture is often embodied in the sumptuous writing implements made for calligraphers. A large Seljuk silver and copper-inlaid bronze inkwell made in the 12th or 13th century is a particularly good example and perhaps a royal commission.

The decorative scheme includes the signs of the Zodiac, roundels with courtly subjects and three inscriptions from the maker reading Amal-e al-Naqqash al-Khademin Amal-e Zaki – translated as ‘the work of the courtly painter, Zaki Bani or Raki Bani’. The estimate is an affordable £800 – £1,200.

A moulded funerary tile with copper lustre decoration, probably made in Kashan in the late 15th or early 16th century, was published in a monographic publication about Iranian copper lustre creations post-Mongol invasion and is bound to attract serious scholarly interest.

Tiles such as this one are hard to come by and they are mostly in private and museum collections. They shed light on a complex chapter of Iranian history, emerging from the new world order of the Mongol invasion, when the production of lustre wares (which flourished in Iran from the 12th to the 14th centuries) had slowly resumed.

Funerary tiles of the Timurid period are often inscribed with Persian verses commemorating the deceased, and in this case, providing factual details like the name of the deceased (Mir Muhammad) and date of their death (three days before Nouruz). From the well-known collection of Arthur Sackler (1913-1987), it is expected to bring £2000-4000.

The auction, put together by the Head of Department Beatrice Campi, aims to bring seasoned and new collectors on an imaginary discovery journey with works of art from acrossthe vast geographic extent of the Islamic and Indian lands.

The sale will be on view at Chiswick Auctions’ new premises at The Barley Mow Centre.

“Our journey starts in Islamic Spain with polychrome-painted wooden beams and an Alhambra-style lion-shaped fountain spout; we arrange a stopover in Iran, with its wonderful medieval ceramics, Qajar polychrome-painted enamels and lacquerware; and lastly, we travel all the way to Myanmar with some fine Burmese silver bowls, and Indonesia with a collection of wayang kulit figural shadow puppets,” Campi said.