The strength and weakness of a language and its respective nation are closely interrelated, when one goes down—so does the other, and vice versa.

When asked about the most horrific events of the 18th century, German leader Otto von Bismarck replied, “the English colonies in North America have adopted English as their official language,” an expression of his disappointment that colonies with large German communities had embraced English as their official language instead of German.

Language is what marks the cultural identity of a nation and defines the allegiance of its people, as most nations are united by one mother tongue that creates or represents the strongest bond between their citizens. This pertains to many nations in the world in which a mutual exchange of being named after the language or the language being named after the people exists, such as Chinese, French, Arabic, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and so on.

Since language is an empowering tool for other nations to transfer their cultures and a reservoir for their thought, literature and history, it is a subject of pride for every nation, and the Arab nation is no exception.

Arabic plays a pivotal role in developing the Arab character culturally, intellectually and psychologically in the past, present and will continue to do so in the future, and as language is the anchor of a nation’s unified identity, its loss foreshadows a society’s disunity and potential demise.

Arabic’s voyage through history

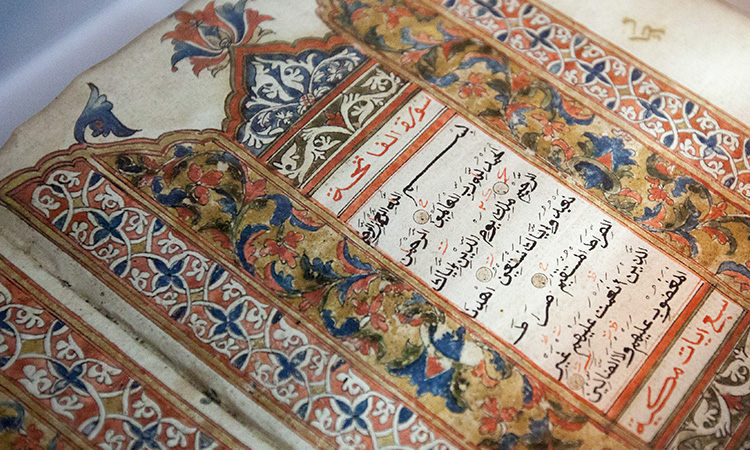

A powerful and versatile language in the pre-Islamic era, Arabic, in which the Qur’an was revealed, grew exponentially as a sacred tongue, expanding beyond being the language of one nation to becoming the language of all nations that embraced Islam as a religion. And so, Arabic became the vernacular for religious observation and acts in Islam, and the fundamental means to a better understanding of the Qur’an; a unique feature that is rarely found in other languages.

Historically, the spread of Arabic was linked to Islamic conquests. I am particularly referring to the remarkable status the language had during the peak of Moorish rule in Andalusia (present-day Spain and Portugal). Universities, literature, art, music and distinctive Arab architecture flourished at a time when the rest of Europe was suffering under mediaeval decadence and the Church’s control.

Royals, rulers and elites sent their children to study in Arabic-speaking universities in Andalusia. Scholars such as Ibn Rushd, Al-Khwarizmi and others were well-known across Europe and formed a springboard for the Renaissance. Centuries later, things relapsed: the Islamic rule of Andalusia collapsed and then Arab countries fell victim to an era of Western colonisation, in which, naturally, the Arabic language declined.

With the reversal of the relationship between the conqueror and the conquered, the tide turned against the Arabic language, and Arabs began to feel the pressure to learn the language of their colonisers.

The aftermath of colonisation

With technology dominating the Arab world’s economy and politics being controlled by Western powers, many Arabs over the last few decades have been educating their children in English, as a prerequisite for employment and access to technology.

In Arab countries with medium or high population density, such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Syria and others, Arabs were able to relatively withstand linguistic challenges. The situation differs, however, in low-population countries such as Qatar, the UAE and Kuwait, whose citizens account for 20% of the total population, with the vast majority being expats from different countries around the world. And so, alarm bells are ringing to warn of threats facing our mother tongue.

In Qatar, we have always been strongly rooted in our Arabic identity and our belonging to the language, which embodies our past, present and future.

As a country and as a people, we understand the threats facing this magnificent language. The responsibility our identity and history placed on our shoulders dictate that we must act to fight the threats facing our mother tongue, particularly due to the increasing number of universities and schools that offer education in foreign languages to meet the unavoidable scientific, economic and political expectations.

It is due to this that Qatar has issued Law No. 7 of 2019, which requires everyone to use the Arabic language in their daily work transactions and meetings.

The decree is excellent in principle and its implementation would effectively contribute to increasing the presence of Arabic in the community, but it has not been fully enforced so that it achieves the desired goals.

One of the first topics that Qatar’s first ever elected Shura Council discussed was the challenges facing the Arabic language. I was invited to the plenary session on this topic and stated categorically that the language should constitute our cultural security. Everyone responded positively to this proposition, and it found great resonance with public opinion in both traditional and digital media. The matter is still the subject of ongoing debate and discussion.

Preservation of identity

Arabic is not just a tool for communication, rather it is our identity, our past that preserves our heritage and the history of our ancestors; it is the language of our faith, without which our religious observance will be incomplete; it is our future, without which we lose what sets us apart as a nation and what connects us with our past; and it is our present, without which we cannot be described as a nation.

Arabic has influenced several other languages, in fact, its impact far exceeds that of many others. Numerous languages are written in Arabic letters and contain a myriad of Arabic vocabulary, such as Urdu, Persian and Swahili. There are other languages that contain thousands of Arabic words and structures, such as Spanish, Portuguese and Maltese. A more limited impact of Arabic is also seen in other Indo-European languages.

The call to preserve the vernacular does not mean in any way that other languages should not be learned. It is a fact that learning foreign languages is a necessity, due to the plethora of developments in every sector and the world’s transformation into a global village. Ultimately, languages are a living organism that interact, influence and converge with each other; such has been the case throughout history, and it should stay that way.

The deep concern we have over our mother tongue being replaced with or weakened by foreign languages, especially English, is shared by many other nations. The French, the Germans, the Spanish and others have the same worry and have taken measures to preserve their national languages from becoming frail or lost.

Since 1973, Arabic has been one of the official languages of the United Nations, along with English, French, Spanish, Russian and Chinese, which testifies to its global standing and impact, as well as the rigour and demands that more efforts are put in to preserve and promote it.

Arab expat communities who live abroad and risk the loss of their mother tongue must bear in mind all these dimensions of the Arabic language, and be more active in maintaining this great vernacular by teaching it to their children as their commitment to both their past and future.

Dr. Hamad bin Abdulaziz Al-Kawari is a minister of state with rank of Deputy Prime Minister and the president of Qatar National Library.

Follow Doha News on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and Youtube