The buzzing sounds of Boeing’s B-29 Superfortress, dubbed Enola Gay, covered the skies of the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

Its residents did not know that the seconds prior to that would be the last before their home, as they knew it, would no longer exist – neither would their friends or relatives.

Seconds later, a large intrusive light and a massive mushroom cloud invaded the heart of Hiroshima – and with a blink of an eye what was once home had turned into rubble.

The United States of America unleashed horrors – and mankind’s first ever atomic bombing – on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 August and 9 August 1945, respectively.

Japanese residents were entangled in the events of World War II in which states across the world joined either the Allies or Axis, in a fight against each other.

In May 1945, the Allies (the US, the UK, Soviet Union, and China) defeated Germany, two months before the completion of the atomic bomb. War with Japan, however, persisted as part of the opposing Axis powers in WWII.

The surrender of the Empire of Japan was announced by the Japanese emperor on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the horrors of World War II to an end.

Fatal impact: Little Boy

The first 15-kiloton atomic bomb, “Little Boy”, was detonated 500 kilometers above the city on August 6, 1945, at 8:15 am Temperatures near the hypocenter reached 3,000 to 4,000 degrees Celsius as a result of the explosion. At half that temperature, an iron bar melts.

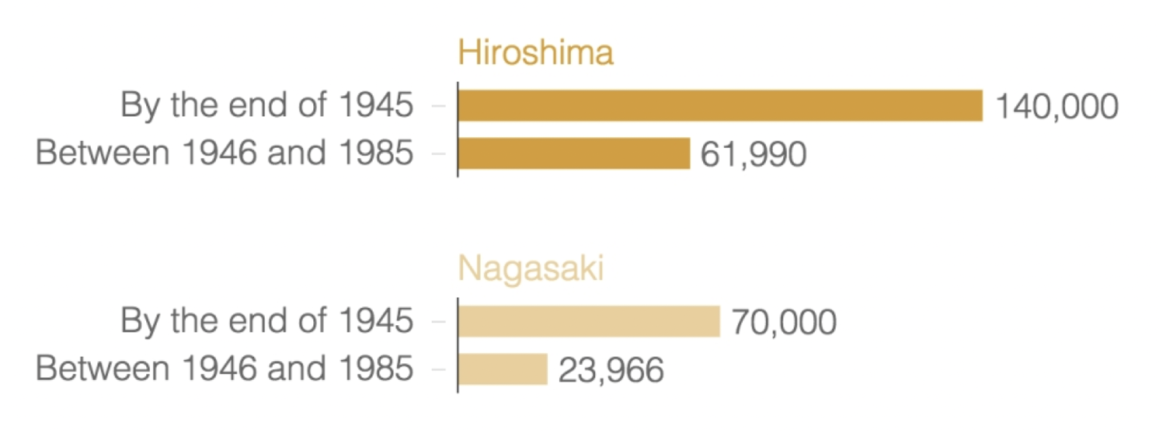

The explosion killed an estimated 140,000 people instantly, and tens of thousands more died subsequently from radioactive exposure.

Second blow: Fat Man

A second B-29 detonated another atomic bomb on Nagasaki three days later, killing around 40,000 people.

There was no imminent Japanese surrender after the first bomb.

On 9 August, Major Charles Sweeney piloted the B-29 bomber, Bockscar, from Tinian. Sweeney was redirected to Nagasaki by thick clouds above the primary target, Kokura.

The plutonium bomb “Fat Man” was dropped at 11:02 am that morning. The bomb, which was more powerful than the one used on Hiroshima, weighing an estimated 10,000 pounds and was designed to cause a 22-kiloton blast.

Nagasaki’s terrain, which was situated in small valleys between mountains, restricted the bomb’s effect, limiting the destruction to 2.6 square miles as opposed to Hiroshima’s 5 square miles.

“Fat Man” exploded about 500 meters above Nagasaki, where an estimated 240,000 people lived, among them Qatar resident Yuki Murakami’s family.

The city was turned into a burnt-out “atomic field,” and by the end of 1945, an estimated 74,000 people had died.

Zaibai Nin, Murakami’s great grandfather, painted the scene of still charred bodies scattered all around the city, particularly near the Nagasaki station, the closest point to the bombing drop scene, Murakami told Doha News.

Her great grandparents immigrated from China to Japan, where her grandparents were then born and raised after getting the Japanese citizenship.

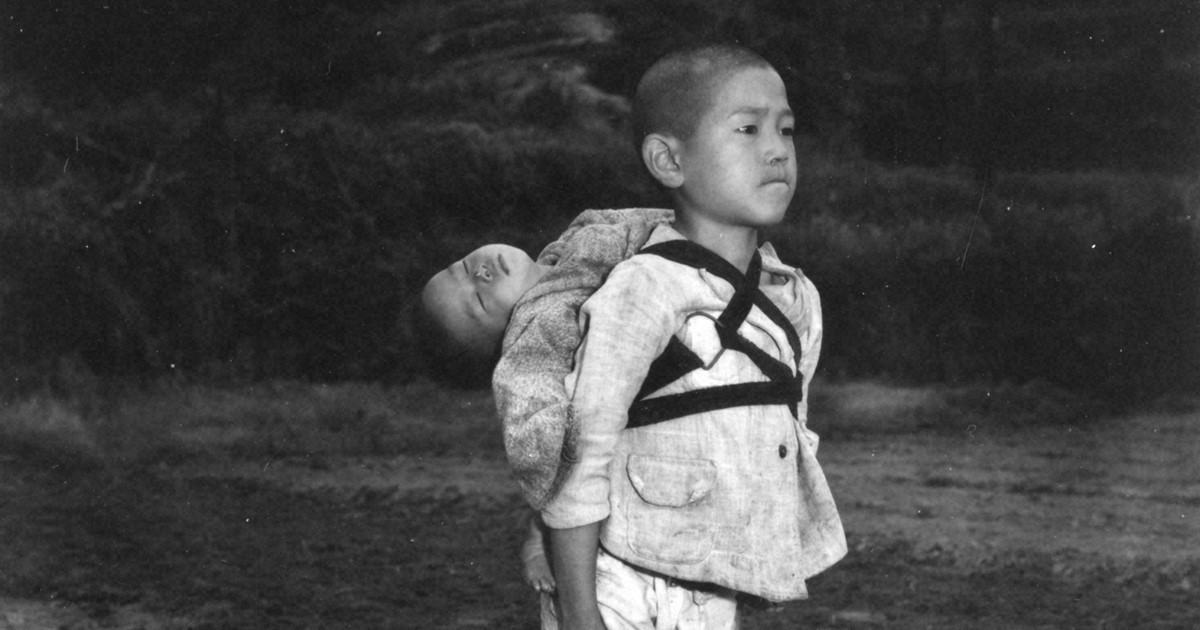

Mounting on top of lingering horrific memories is Murakami’s grandmother, Setsumi Chin, who was a mere ten year old girl when she witnessed the streets she spent her childhood playing in become a black blanket overnight.

During the war, after Hiroshima was bombed, the women and children were moved from the cities to the countryside for safety. Chin was among the children who moved. She only went back to the city after a few days of the bombing, burdened with the news already.

“She told me that the city she knew was completely destroyed. It was gone, vanished,” Murakami told Doha News.

Murakami’s paternal grandmother, Kazuko, thirteen years old at the time, was at her house during the explosion. However, she was of the lucky few who survived, with only the glass shattering in her home. Some of her family members were not so lucky though.

Estimating the overall casualties in the Japanese cities as a result of the atomic attack has been extremely difficult.

The extensive destruction of civil installations like hospitals, fire and police departments, and government agencies, combined with the state of complete confusion immediately following the explosion, and the uncertainty about the actual population prior to the bombing all contribute to the difficulty of estimating casualties.

Pearl Harbour attack

Pearl Harbor is a United States naval colony near Honolulu, Hawaii, where Japanese forces launched a surprise attack on 7 December 1941, which the US claimed it was retaliating against. On that Sunday morning, just before 8 am, hundreds of Japanese fighter planes landed on the base, destroying or damaging over 20 American navy vessels, including eight battleships, and over 300 aeroplanes. The strike killed almost 2,400 Americans. President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan the day after the attack.

After 16 years of uncovering documents through the Freedom of Information Act, journalist and historian Robert Stinnett claims in his book, “Day of Deceit”, that US government leaders at the highest level not only knew a Japanese attack was imminent, but also deliberately engaged in policies designed to provoke the attack, in order to draw a reluctant American public into a war.

Some historians and policy experts now claim that official government stances over the years that led to the Spanish-American War, World War I, the Vietnam War and other conflicts were ‘deliberate misrepresentations’ of the facts in order to rally support for wars that the general public would likely not support otherwise.

America’s ‘controversial’ agenda

Nobel Prize laureate Albert Einstein’s E=MC2 birthed the “Atomic bomb project” idea in 1939. Later in 1942, the Manhattan Project produced the world’s first nuclear weapons led by the US and supported by the United Kingdom and Canada.

The Manhattan Project was the codename for the secret US government research and engineering programme during World War II, that gave rise to the world’s first nuclear weapons.

Former President Franklin Roosevelt assembled a committee to look into the possibility of developing a nuclear weapon upon receiving a letter from Einstein in October 1939, in which he warned that Nazi Germany was likely already in the works of developing a nuclear weapon.

Military advisers to the US president at the time, Harry S. Truman, warned that such a war would lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands with Truman himself claiming it might cost up to a million casualties.

After Japan’s failure to provide the US with a response regarding Truman’s “prompt and utter destruction” threat which would follow if Japan did not surrender unconditionally, the American president authorised the use of the bomb on the country.

Experts argue that the American refusal to modify its “unconditional surrender” demand needlessly prolonged Japan’s resistance.

Little Boy and Fat Man were used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with Manhattan Project personnel serving as bomb assembly technicians and weaponeers on the attack aircraft.

Proponents of the A-bomb, such as the Truman administration’s secretary of state, believed that its catastrophic power would not only end the war, but would also place the US in a dominant position to shape the postwar world.

Experts have argued that the destruction of the Japanese cities were not done solely to force Japan into surrender and put an end to World War II. Rather it was to carry out an experimentation of the newly developed deadly weapon and cement its foothold as a world power in the face of another aspiring superpower, the Soviet Union.

In his book “Nuclear Weapons: A Very Short Introduction”, Joseph Siracusa described the developments of the Manhattan Project’s “discovery” and experimentation of fission as a shift “from laboratory to the battlefield”.

The bomber, piloted by the brigadier general in the US Air Force, Colonel Paul Tibbets, flew at low altitude on automatic pilot before climbing to 31,000 feet as it neared the target area in Hiroshima to release Little Boy.

In “The Atomic Café”, Tibbets said that they were told by authorities to select “virgin targets” in Japan to bomb, adding that the group (army) allegedly did not know the reason behind the targeting of virgin lands for carrying out the bombing.

Evidence has been disclosed, alluding to the knowledge that Japan was in fact ready to surrender prior to the US’ “unconditional surrender” demand.

By mid-summer of 1945, Japan had experienced tragic ramifications of the war.

According to an opinion piece published on The Washington Post, the way in which the Allies’ intelligence understood the situation at the time was detailed in a report to the American and British Combined Chiefs of Staff, made public in 1976:

“The increasing effects of sea blockade and cumulative devastation wrought by strategic bombing […] has already rendered millions homeless and has destroyed from 25% to 50% of the built-up area of Japan’s most important cities […] A conditional surrender […] might be offered by them at any time […]”

“The Japanese code had been broken early in the war,” the report read, adding that “faint peace feelers appeared as early as September 1944.”

Truman’s diary, uncovered in 1978, detailed a crucial “intercepted” message that read: “The telegram from the Jap emperor asking for peace.”

William D. Leahy, who served as chief of staff to the president and presided over the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wrote in his diary mid-June: “At the present time […] a surrender of Japan can be arranged with terms that can be accepted by Japan and that will make fully satisfactory provision for America’s defence against future trans-Pacific aggression.” Afterwards, Leahy would express that “the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan […]”.

Legacies of tragedy

The American government implemented the Press Code, a censorship code that limited what journalists were allowed to print about the bombings. This code was finally lifted in 1952 with the signing of the San Francisco Treaty, which restored Japan’s sovereignty.

Atomic bomb survivors known as “Hibakusha“, continued to suffer the consequences of radiation for years on end.

In 1947, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) was established to investigate the long-term effects of radiation on Hibakusha.

In 1975, the ABCC was replaced by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation. According to the study’s findings, women are two times more likely than males to get solid tumours as a result of the radiation exposure. This was because radiation exposure caused more sex-specific diseases, such as breast cancer.

The study also found that the younger people who were exposed to radiation were more likely to die from cancer. Especially young girls, who were twice as likely as their male counterparts to develop cancer.

“My grandma had to build her whole life again and restart at such a young age. Some of the family members dear to her were gone. Because they were exposed even if they initially survived, many got cancer and leukaemia after a few years,” Murakami told Doha News.

According to a study, their exposure to radiation increased the number of stillbirths, miscarriages, premature births, birth abnormalities and growth issues. Another study discovered that radiation exposure hastens menopause.

They were also subjected to social stigma. Due to a general lack of understanding of radiation, the Hibakusha became the subject of marginalisation and seen as social outcasts in Japanese society. They were denied shelter and food and were barred from public venues and work possibilities.

Female Hibakusha endured the most discrimination. Women have reported feeling violated while being examined by foreign scientists at the ABCC. Women were already thought to be ‘polluted’ due to their ‘reproductive roles’ before the atomic explosions. They were, at the time, considered as doubly tainted and therefore subject to more discrimination due to the supposed impurity of radiation exposure.

Hibakusha women carried the burden of tainted affiliations to their children’s sterility and any birth abnormalities. Dubbed as a “female” disease, affected women were blamed for the expansion of leukaemia.

All of these things combined to make female Hibakusha less desirable for marriage.

“When grandma Chin was trying to get married, if people knew she’s from Nagasaki, she would be discriminated against because they would assume she was exposed to the atomic bomb. Her life became harder in so many aspects,” said Murakami.

They were seen to be unfit to marry and have children. This was tough to deal with in a society that put a high emphasis on a woman’s ability to fulfil these societal expectations.

There was no way of knowing what the bomb’s long-term repercussions would be, or whether it would disproportionately harm female Hibakusha.

It was only until relatively recently that the Japanese government stepped up to support those affected by the bombs.

“Only after the 2000s, the government started to admit to the facts of the events and then they started issuing this card so they [Hibakusha] can have more benefits from it,” Marakundi told Doha News.

“My grandmother was given a medical health card that grants the victims free healthcare among other things, meant to make their lives easier.”

Residents exposed to the radioactive “black rain” that washed over Hiroshima in the blasts’ aftermath were finally recognised as Hibakusha and granted the medical benefits guaranteed to other A-bomb survivors. Under the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Assistance Act, survivors were entitled to periodic physical examinations, screenings and medical treatment.

The intense fires created around Hiroshima by the bomb carried large quantities of ash into the atmosphere. The result was a ‘black rain’ which fell 1-2 hours after the explosion. This rain, which almost had the consistency of tar, was a combination of the ash, radioactive fallout and water.

“It not only stained skin, clothing, and buildings, but also was ingested by breathing and by consumption of contaminated food or water, causing radiation poisoning,” reports detailed.

Fear of erasure

In an attempt to eradicate the lingering remnants of one of humanity’s deadliest attacks, the US issued Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) Directives to the Japanese government in order to curb Tokyo’s “militaristic nationalism” aspirations.

A day before Japan’s surrender, the occupation of the southeast Asian country began on 14 August 1945.

In Japan, the position was known as GHQ (General Headquarters), as SCAP also referred to the occupation’s offices, which included several hundred US civil officials and military personnel. Some of these individuals wrote the first draft of the Japanese Constitution, which was eventually passed by the National Diet after a few revisions.

“It’s kind of like brainwashing, I would say, because after the war ended in Japan, GHQ Global, from America, tried to control Japan. Those people tried to fix the image of America and brainwashed our generation to reverse their image,” Murakami told Doha News.

Directives from GHQ led to other wide ranging political and economic changes in Japan, such as the purge of what they deemed as “undesirables” from public office, land reforms and the dissolution of the zaibatsu.

Fearing the dissipation of her country’s tragic past into just museum monuments and history books, Murakami said: “We are the last generation hearing real voices from the seniors.”

Pushing for more to be done around raising awareness, she said: “As time went by, it started to fade. I am interested, but I don’t really know much about it. And I’m sure that in our younger generation, the awareness has faded a lot too.”