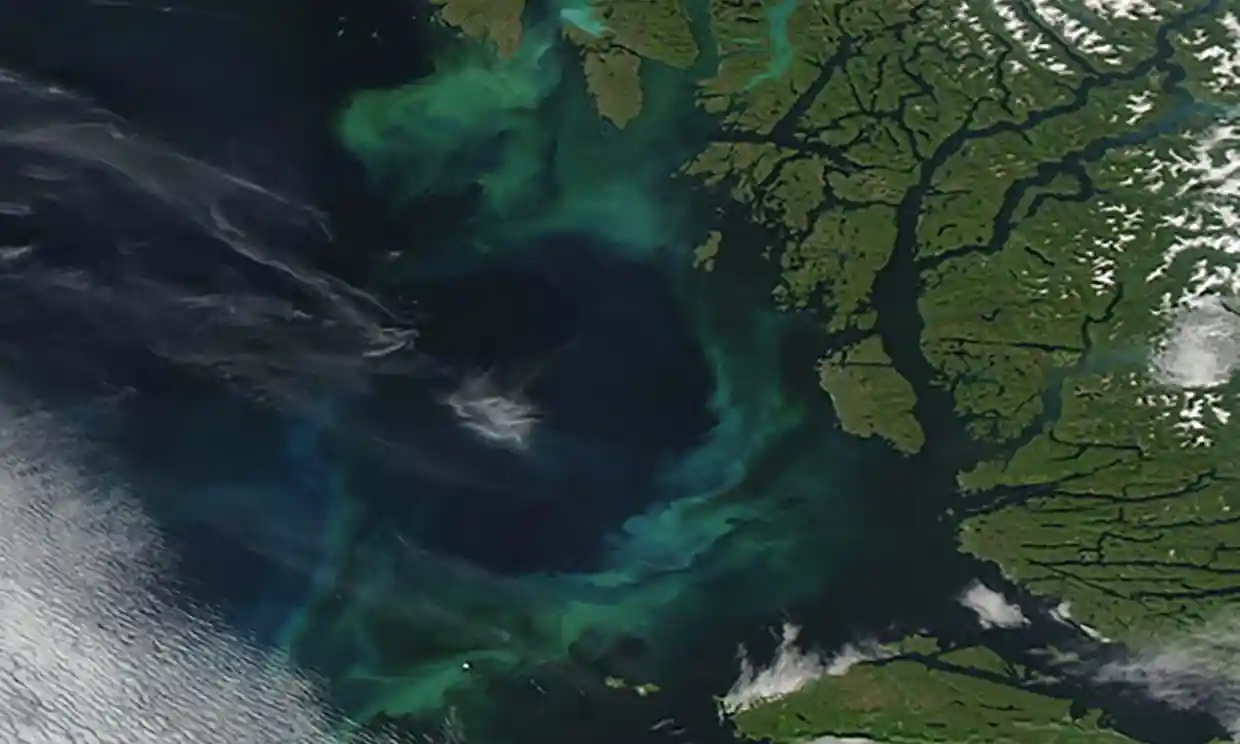

NASA satellite images have uncovered sea colour changes due to altered plankton populations.

A recent scientific study suggests that the earth’s traditionally blue oceans are experiencing a steady shift in colour, trending toward an ever-greener hue, due to changes in global plankton populations.

The transformation is particularly notable in low-latitude regions near the equator, it stated.

BB Cael, a prominent scientist at the National Oceanography Centre at the University of Southampton and the author of the study, which was published in Nature, explains the significance of this colour shift.

“The reason we care about this is not because we care about the colour, but because the colour is a reflection of the changes in the state of the ecosystem.”

Historically, scientific exploration has been centered on the ocean’s increasing greenness, a reflection of the chlorophyll found in plankton, to ascertain the evolving patterns of our climate.

However, Cael’s team adopted a different approach, meticulously scrutinising 20 years of observational data from NASA’s Modis-Aqua satellite. Their focus was on discerning the changing patterns of the ocean’s colours, including red and blue, throughout the entire spectrum.

The team’s unique research approach acknowledges that plankton of different sizes scatter light diversely, and plankton possessing diverse pigments absorb light in distinct ways.

Such shifts in colour may provide scientists with a clearer understanding of changes in global plankton populations, a critical element to the health of oceanic ecosystems, given that phytoplankton forms the foundation of most marine food chains.

Cael’s team matched these shifts in colour with predictions derived from a computer model simulating ocean conditions in a world unaffected by human-caused global warming. The results were revealing.

“We do have changes in the colour that are significantly emerging in almost all of the ocean of the tropics or subtropics,” said Cael.

These observed changes span 56% of the world’s oceans—an expanse larger than all the land masses on Earth. In most areas, a visible “greening effect” is evident.

However, the expert also pointed out fluctuations in red or blue colourings in various locations.

“These are not ultra, massive ecosystem-destroying changes. But this gives us an additional piece of evidence that human activity is likely affecting large parts of the global biosphere in a way that we haven’t been able to understand,” he said.

While this study presents a tangible new consequence of a changing climate, the depth of these changes and the precise mechanisms driving them are yet to be fully understood, according to Michael J Behrenfeld, an ocean productivity researcher at Oregon State University, who was not involved in this study but spoke to The Guardian.

“Most likely, the measured trends are associated with multiple factors changing in parallel,” said Behrenfeld. For example, the rising abundance of microplastics in the ocean, like other particles, may be influencing light scattering.

Behrenfeld emphasised that only with a clear understanding of these intricate processes can scientists begin to interpret the ecological and biogeochemical implications.

To that end, NASA is poised to launch the advanced satellite mission, PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem), in January 2024. This mission will measure hundreds of oceanic colours rather than a mere handful, paving the way for further exploration of this phenomenon.

“Making more meaningful inferences about what the changes actually are ecologically is definitely a big next step,” Cael concluded on a hopeful note.