The 74th Nakba anniversary this year coincides with global outrage at Israel’s assassination of renowned Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh.

Israel was founded as an ethnocentric Jewish-majority apartheid state on 15 May, 1948, at the cost of the forced expulsion of approximately 750,000 Palestinians.

Nakba Day has since become an annual commemoration of the tragic, ongoing event.

The term “Nakba” refers to the systematic ethnic cleansing of two-thirds of the Palestinian population by Zionist paramilitaries between 1947 and 1949, as well as the near-total annihilation of Palestinian society as we know it.

In a series of mass killings, including more than 70 massacres, Zionist forces had taken over 78% of historic Palestine, ethnically cleansed and destroyed approximately 530 villages and cities and killed an estimated 15,000 Palestinians.

This year marks the 74th anniversary of the Nakba, or Palestinian dispossession and loss of homeland.

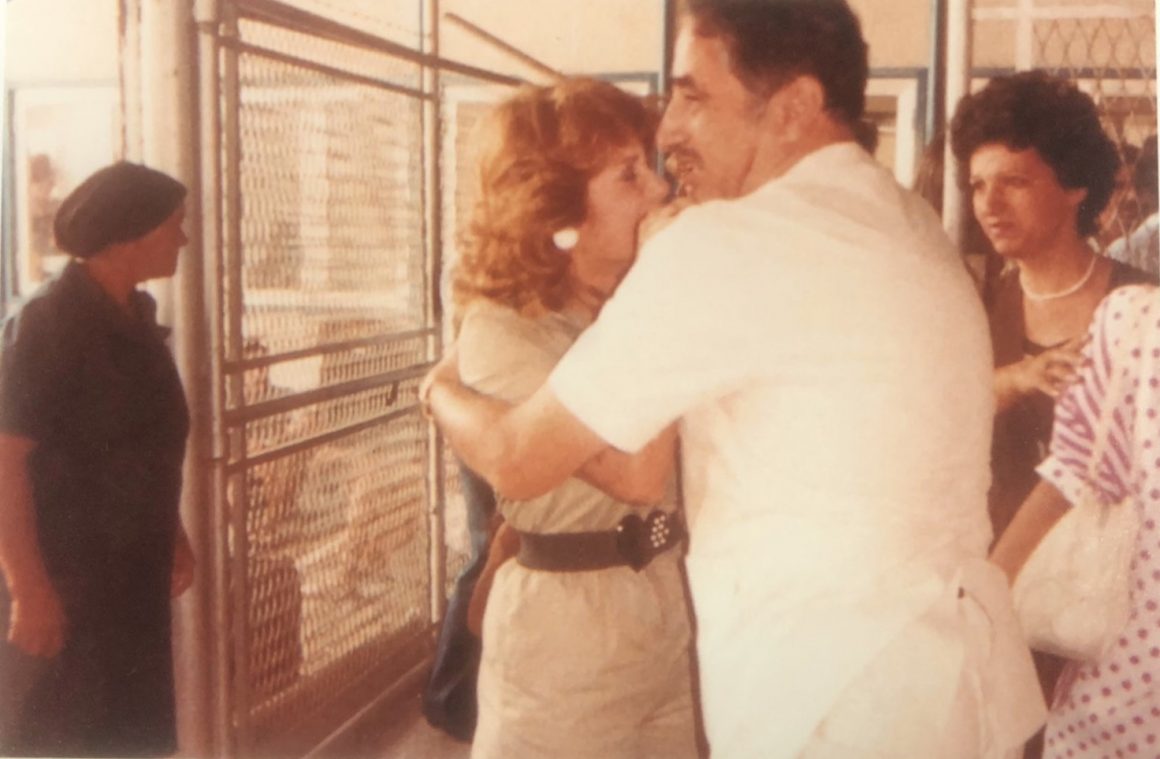

Doha News has spoken to Palestinians in Qatar whose families have lived in the country for generations, about their own Nakba stories, and what ‘home’ means to them.

Mira Al-Bast

“As Palestinians, we have to constantly learn about our history so that it never dies, we have to learn about our identity and we have to voice out our identity to people.”

Al-Bast is a 24-year old financial analyst living in Qatar. She was born in the United States, but has spent all of her life in the Gulf state. Her family were exiled from Yaffa.

“My mother recognised that, unfortunately, as Palestinians we do not get equal opportunities and face a lot of struggles by merely existing. She wanted to make things just a bit easier for us and I recognise the privilege that we have in that sense.”

Her grandmother was only five years old when she was exiled from her home in Palestine. She moved on foot to Syria with her family while trying to escape the brutality of Israelis and the settlers who were coming to take away their homes.

Before leaving the home she never got to see again in Palestine, Al-Bast’s grandmother watched her uncle die after stepping on an explosive that Israelis had thrown into their yard.

In her younger years, the grandmother lived the majority of her childhood in Syria, up until the age of 17.

“At some point they lived in a mosque in Syria as they were with the UNRWA camp. Her sisters could not attend school, one of them had to work in order to provide.”

While Al-Bast’s grandmother continued school, she learnt how to make dresses and clothes because her family could not afford to buy anything.

“My grandmother instilled in us and herself the Palestinian identity.”

Sometime during 1959, her grandmother arrived to Qatar as a 17-year old girl.

Before the Nakba, Al-Bast’s grandfather was only 14 years old when his dad sent him alone to Egypt to study.

He came from a known family of traders in Palestine and so his parents did not want him to be dependent on the family wealth, and hoped he would build a career and identity for himself while in Egypt.

When the Nakba happened, Al-Bast’s grandfather was never able to return, and lost all contact with his family. He was forced to relearn who he was separate from who his family were, and was only able to reconnect with them decades later by looking them up on facebook.

“We are Palestinians in exile, anyone who is not on Palestinian land is in exile. Exiled from our homes. We have to work extra hard to show people that we are very well educated, we are capable, we are accomplished, we are smart, we are fighters and we fight for our story and our existence. We are resilient and we are here.”

To Al-Bast, home has many definitions.

“Home can be a person, a house, a family. In the context of home as a sense of belonging or a sense of identity tied to a particular land, Palestine has been my home even though I have never been[to it]. I just know my history and I know what my family has endured and I know who Palestinians are and I know that Palestine, no matter what, is my home. This is where eventually my roots will grow.”

“Qatar has provided a home to me and my family. It has provided shelter and whatever it can to make this a home for us.”

However, to many Palestinians, including Al-Bast, ‘home’ is more than just shelter.

“I know that I am not Qatari, which is why this is not my home. I want my land, I want to live amongst other Palestinians and do things that Palestinians do. Going into the farms, Masjid al-Aqsa, and feeling like this is my place and I’m here to stay.”

Many families moved to Qatar in hopes for a better life. However, no matter the connections they may have to the country and its people, non-nationals are required to leave once they retire unless granted permanent residency or a Qatari citizenship, which is a rare occurrence.

“Eventually, we are going to end up leaving Qatar. We’re not Qatari or permanent residents here so there will come a point in time where we will have to relocate. Again.”

Mariam*

“This is not home. I plan to die in Palestine.”

Mariam, who prefers to remain anonymous, is a 29-year old Palestinian women born in Qatar, whose family origins are from Yaffa, Palestine.

Her father’s family have been in Doha for more than 70 years, rendering her among the third generation in her family to be born in the country.

In 1948, both of Mariam’s paternal and maternal grandparents were expelled from their homes in Salama village, Yaffa. They fled to Jordan and settled there, before moving to Saudi Arabia then eventually Qatar.

Like many Palestinians, when they left their homes, they had nothing but their clothes on their backs, their keys and deeds to their houses thinking that the displacement was but temporary and that they’d be back in their homes in a few days time.

This mindset remained over the years every time her grandfather was offered a business opportunity, legal documents, and even a Qatari citizenship that he rejected. He refused to own land in any country due to his firm belief that he would return to his own in Palestine.

“Why own a land or have a citizenship other than Palestinian when my country is waiting for me to return to it?” He would often say.

“My grandfathers died in exile. My grandmothers still hold on to the keys and tell us their stories and how life was back then.”

As Mariam grew older, her connection to Palestine grew stronger. The more she tried to find somewhere to belong to, the more she realised Palestine was the only place she felt a connection to, despite having never been there.

To her and many Palestinians in exile, having other friends from the Palestinian diaspora, even if online, provided them with the sense of belonging that she always found herself looking for.

She recently identified an unshakeable feeling of homesickness that took her a while to pinpoint. “I feel homesick but it’s a place that I’ve never been to yet. It’s a place that I still need to experience. That’s how I feel towards Palestine.”

“Its like you have a mother somewhere but you’ve never met her and you only have pictures of her. The more you look at the pictures the more the yearning gets to you.”

To Mariam, the concept of home embodies “safety; belonging; community; security and love.” These elements however, she has struggled to find in Qatar.

“I am constantly reminded that this is not where I belong. Ever since I was a child and could not comprehend the difference between nationalities, I had to learn the hard way that I am not part of this community even though I was born here and Qatar is all I know.”

Mariam told Doha News that she often does not feel safe to express herself or her views.

“My only community here is the Palestinian community, family and friends. I do not feel secure to settle down here nor do I want to, the same applies to my family and most Palestinian families that I know who are seeking to leave and seek refuge in other countries.”

“We are treated just like any other “ajnabi” (foreigner) with disregard that we likely have nowhere else to go.”

She witnessed firsthand the difference between a “watheeqa” and a Palestinian holding a Jordanian temporary passport with “Abnaa’ Gaza” stamp on the back.

“We are told that we are valued but the reality is we are erased and forgotten.”

Her relationship with Qatar, however, is not as simple as that.

“I do love Qatar, I am grateful for even the privilege of being here. I do feel safe in a sense, but I am privileged and I acknowledge that privilege.

But it’s still not home. I don’t feel like I belong, still. Even though I love it, I feel like I am rejected, I am not one with this country, or its community.”

Noura*

“Home is wherever I’m accepted for who I am.”

Noura, 21, is a journalism student studying in Qatar, who is from both Al-Jiyya and Bir Al-Sabi.

Her family habe been in Qatar since the early 70s. However, Noura was born and raised in Egypt.

She has been to Gaza several times in 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2014.

The reason her family went their so often was because after their exile, they moved to Gaza, so their houses are there, and her father was born there. “We only went to Gaza because we never had access to go to other places in Palestine.”

After the Nakba, her maternal grandfather moved from Bir Al-Sabi to Gaza. In 1969 he moved again, this time from Gaza to Doha, and started a new life in the Gulf city. Like many of the Palestinians who relocated to the Gulf after the Nakba, he worked as a teacher.

Noura’s paternal grandfather lived in Egypt for almost 40 years. While he was leaving his home in Al-Jiyya and going to Gaza, he thought that it would be only a matter of weeks before returning.

After they left from Gaza to Egypt, they thought it would only be a matter of six months or so. But the months never ended.

“He kept telling himself, a week, two weeks, a month, two months, until years and decades eventually passed.”

Al-Jiyya was ethnically cleansed between 1948 and 1949. According to a 1945 census, the village had a population of 1,230 people.

“Home is wherever I am accepted. Accepted for who I am. I don’t need to put in effort, I don’t need to convince people that I belong here.”

“All Palestinians in exile understand that no matter where we live, be it in Egypt or Doha, the [United] States or wherever, we put so much effort into so much but we’re never considered as a part of the place. Be it your own feelings that you do not belong, or those around you giving you a constant reminder that you do not belong here.”

To Noura, there is currently nowhere she can call home. She feels like she is never accepted fully, and even the fraction of acceptance that she gets, is often after pouring in additional effort that she believes non-Palestinians do not have to do.

“Qatar does not feel like home. I love Qatar, it has given me so much, such as a great education and healthcare. If it weren’t for Qatar I wouldn’t have many of the things I have today. But still, that’s not enough to make it home.”