Oryx, Rainbow, Burger King, Clock. For many years, these Doha roundabouts acted as memorable landmarks and navigation points that have since been replaced with more efficient signaled intersections.

Loved them or loathe them, the junctions were always a talking points. Now, a newly opened exhibition is asking whether the demolition of the roundabouts is destroying part of Qatar’s cultural heritage.

The exhibition, titled Heritage, Research and Art, uses roundabouts as a jumping off point to discuss what constitutes heritage, what aspects of life Qatar residents value and what is worth preserving and what is not.

The collection of research, artist paintings and photos of the roundabouts are open for public viewing at the Hamad Bin Khalifa University (HBKU) student center art gallery in Education City through Sept. 23.

Research

The exhibition combines academic research from University College London-Qatar (UCL Qatar)’s heritage research project with local artists’ interpretations of the changing face of culture in Qatar.

It features key findings from research undertaken by students at UCL Qatar’s Masters program in Museum and Gallery Practice and Archaeology, who examined the cultural value people placed on key roundabouts in Qatar.

They focused on Al Mirqab roundabout in Doha’s once-bustling but now rather run-down old downtown, Dar Al Kutub roundabout near the National Library and Sports roundabout behind Al Saad.

Between September 2013 and January 2014, the students quizzed residents, workers and policy makers through questionnaires and interviews, and searched through archival data to unearth stories, anecdotes and attitudes about these old landmarks to find out if they were valued as culturally important.

Alkindi Al Jawabra took part in the study, examining opinions on Al Mirqab roundabout and, along with Louisa Brandt, is curating the exhibition.

Al Jawabra said that while the roundabout itself had no architectural value, he found that people living and working nearby had lots of memories attached to it.

Fondness dated back particularly to its previous incarnation as Clock Roundabout – not to be confused with Clock Tower (VIP) Roundabout, which has also been removed.

Speaking to Doha News, he said:

“People told us about a speaking clock, which used to tell the time, and it would be a local meeting place for people to hang out, drink karak or tea and just spend time there.”

Older Qataris especially had many memories of the old roundabout, showing they gave it historical and sentimental value, Al Jawabra added.

After the clock stopped working, it was removed by authorities, and the roundabout was re-landscaped and renamed to reflect the surrounding area.

Meanwhile, Oryx, or Al Maha, roundabout on Majlis Al Tawon street, which was removed last year, evoked some of the strongest memories from people.

It was viewed as a key landmark that helped newcomers navigate their way around the city, Al Jawabra said.

Sports roundabout, which is regularly clogged with traffic trying to move across town, is another site that elicts personal memories and stories from residents, which helped to support the study’s concept of heritage as a “living process that takes place through experience, rather than as a list of monuments to preserve.”

Artists’ impressions

The exhibition also features local artists’ interpretations of cultural identity.

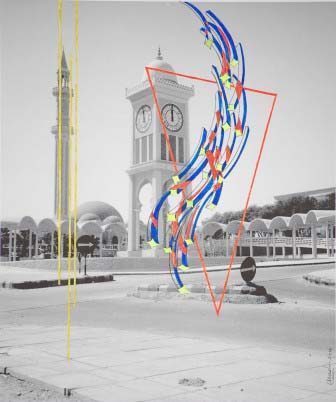

Indian artist Urvashi Gaekwad, who has lived in Qatar for 10 years, uses traditional photographs and superimposes modern images which she describes as “sterile” to show “a loss of culture and history, and hence character.”

“Our cultural history gives us a unique identity, keeping us personally connected and invested in our region. It helps foster growth unique to us and hence by preserving it, prevents us from melting into a human mass of abstract obscurity,” she added.

Dr. Trinidad Rico, former lecturer in Heritage Studies at UCL Qatar and now an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University at Qatar, said that the transformation of Qatar’s old roundabouts has had an impact on society, although many people point out that they were a western import to deal with emerging traffic flow and are not originally a part of Qatari culture. She added:

“In the aftermath of their disappearance, there is a growing conversation in Doha that aims to value the aesthetic and historical appeal of roundabouts, an emerging nostalgia and appreciation that may only have emerged posthumously.”

The exhibition contains an art installation, Permanent Temporalities, by Doha-based artists Christto & Andrew, that shows the changing face of Qatar since the discovery of oil and gas.

Feet in a pair of traditional Qatari sandals sit atop a concrete plinth, lit by LEDs.

The artists aim to show how roundabouts, which were popular meeting places when people walked around the town, are now being replaced by more efficient but less socially interactive traffic signals.

According to the exhibition catalog, the sculpture “questions to what extent technology becomes a factor for the replacement of heritage and furthers the debate of what elements constitute national heritage in Qatar.”

How do you feel about Doha’s roundabouts? Thoughts?

Note: This article was edited to reflect Dr Trinidad Rico’s new position as Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University at Qatar.