If Qatar makes strides in US-Iran mediation efforts, it could bolster Doha’s international reputation as a regional power, writes Samuel Ramani.

Less than two months into his presidency, Joe Biden’s hopes for a swift return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) are hanging by a thread. Iran’s uranium enrichment is 14 times higher than the JCPOA allows.

An Iranian rocket attack killed a US military contractor in Erbil, Iraq on February 15 and the United States retaliated with a strike on pro-Iran militias in Syria, which killed 22 combatants.

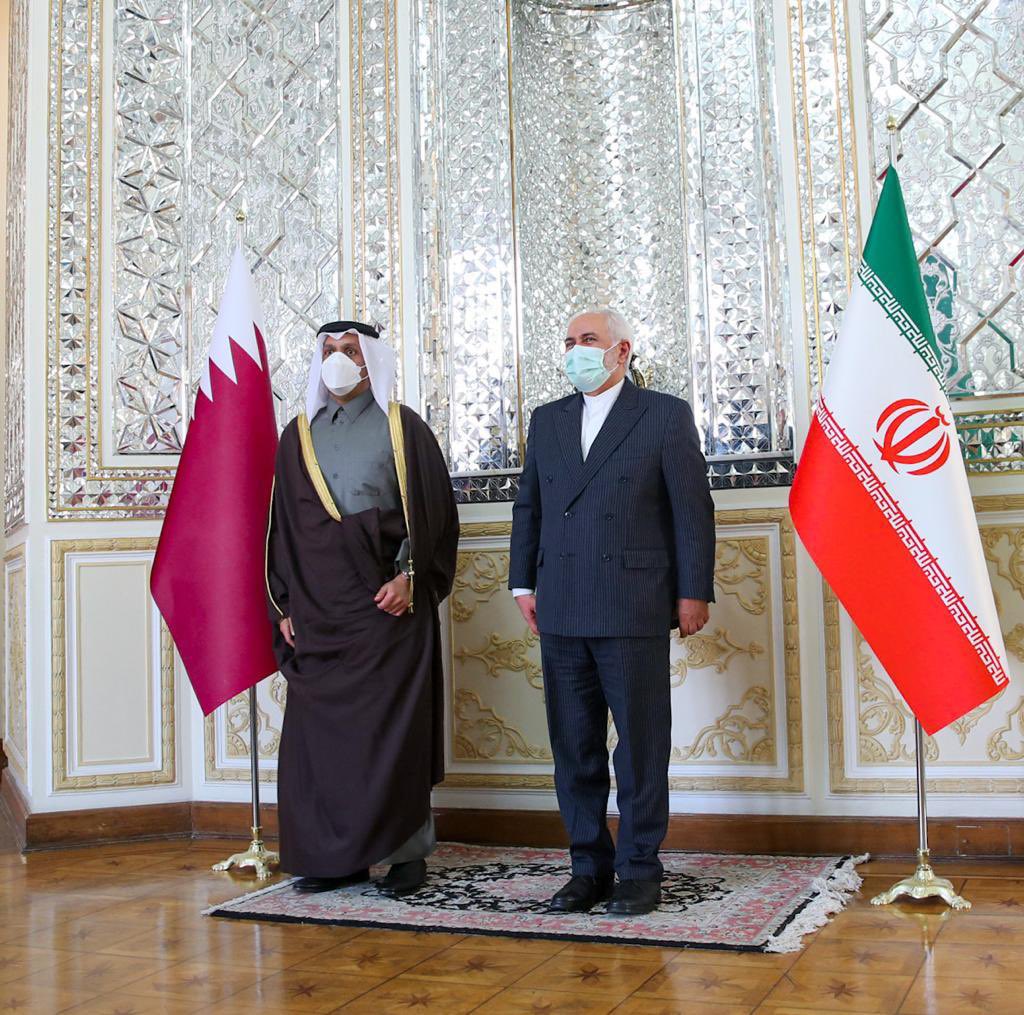

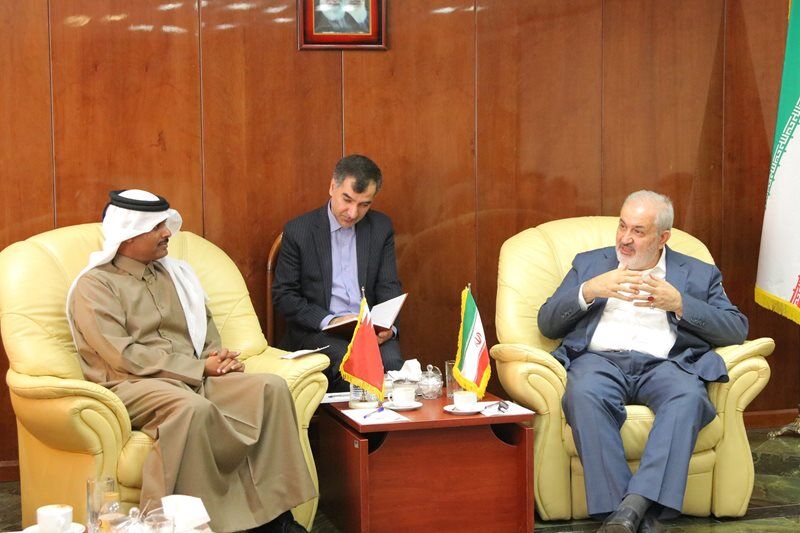

As these tensions caused Iran to reject participation in Europe-brokered nuclear deal talks with the United States, Qatar has emerged as a possible interlocutor between the US and Iran. On February 10, Qatari Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani announced that Qatar was “working on de-escalation through a political and diplomatic process to restore the nuclear agreement.”

Sheikh Mohammed has held talks with US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and US Special Representative Robert Malley on restarting the JCPOA. Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh stated that Iran welcomed Qatari assistance on reviving the JCPOA, while Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu has praised Qatar’s potential to arbitrate between the US and Iran.

In its bid to facilitate US-Iran dialogue, Qatar possesses three crucial advantages.

First, Qatar is a regional power that is trusted by both the United States and Iran. While US-Qatar relations under President Donald Trump were strained by his initial endorsement of the Saudi-led blockade in June 2017, Joe Biden’s election contributed to the January 5 AlUla Agreement that ended the Qatar diplomatic crisis.

Iran’s provisions of food and vital consumer goods to Qatar following the blockade eased frictions in the Tehran-Doha relationship. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif praised Qatar for its “brave resistance to pressure and extortion” after the AlUla Agreement was signed and Sheikh Mohammed has insisted that the end of the Gulf crisis will not change the positive tenor of Qatar-Iran relations.

Second, Qatar has extensive experience with crisis diplomacy in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia.

Prior to the Arab Spring, Qatar brokered ceasefire talks in Yemen from 2007-08, the 2008 Doha Agreement that ended Lebanon’s eighteen-month political crisis and the 2011 Doha Agreement that provided a roadmap for peace in Sudan’s Darfur region.

In April 2017, Qatar brokered the release of 26 of its citizens from Iraq after extensive negotiations with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). More recently, Qatar has chaired US-Taliban negotiations, which have facilitated the drawdown of US forces from Afghanistan and is an active player in conflict resolution efforts in Syria and Libya.

Qatar’s experience as an arbiter and dialogue facilitator could help it ease US-Iran tensions.

Third, Qatar has a network of Arab partners which could facilitate its efforts to broker between the US and Iran.

Oman facilitated dialogue between the US and Iran, which culminated in the 2013 interim agreement and the JCPOA, and recently brokered talks between the Iran-aligned Houthi movement and the United States on ending the Yemen war.

Iraq hosted senior officials from Saudi Arabia and Iran in April 2019, and reportedly acted as a backchannel between Riyadh and Tehran in the fall of that year. Support from Oman, Iraq and perhaps Kuwait, which supports a US-Iran de-escalation and has overcome its recent political turmoil, would significantly benefit Qatari dialogue facilitation efforts.

In spite of these advantages, Qatar’s ambitions of arbitrating between the US and Iran are likely to face short-term setbacks.

As Iran’s presidential elections are coming up in May 2021, hardliners and the IRGC could protract the revival of US-Iran negotiations through destabilising conduct. This gambit, which is aimed at securing a triumph for a hard-line anti-Western presidential candidate, could cause Iran to reject Qatari mediation efforts. Iran’s refusal to accept Qatar’s assistance in the standoff over the seized South Korean Hankuk Chemi tanker in January could repeat itself on the JCPOA.

Read also: Qatari FM meets EU ambassadors in bid to revive nuclear deal

Qatar’s belief that US-Iran dialogue over the JCPOA should be accompanied by regional talks between Iran and its Arab rivals might also struggle to gain traction.

Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif praised Qatar’s calls for regional dialogue as they dovetail with Iran’s Hormuz Peace Initiative (HOPE) collective security plan, but Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates remain skeptical.

As Oman faced backlash from Saudi Arabia and the UAE over its role in the 2013 interim agreement, which came as a surprise to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, Qatar should be wary of a repeat scenario.

The January 5 AlUla Agreement and subsequent events such as Qatar’s engagements with the UAE and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, are positive developments, but Qatar should not assume that the anti-Iran bloc within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) will welcome its mediation efforts.

While Qatar might be uniquely suited to assist a reconciliation between the US and Iran, it needs to view this as a long-term objective rather than immediate goal.

Qatar should also work in concert with great powers, such as France, Germany and even Russia, which seek to de-escalate tensions between the United States and Iran. It should also closely consult with its GCC counterparts in order to avoid setting back the Gulf reconciliation process.

If Qatar eschews unilateralism and approaches US-Iran dialogue in an incremental fashion, it could bolster its international reputation as a regional power that contributes to the stability of the Middle East.

Samuel Ramani is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at the University of Oxford and a non-resident fellow at the Gulf International Forum in Washington DC.