by Muhammad Muneeb Ur Rehman

After some four months of COVID-19, Gulf states are now haemorrhaging money and workers. Doha News analyses the region’s economic stability.

Let’s be honest, 2020 got off to a rough start for Gulf countries, with oil prices nosediving after Saudi Arabia’s economic fallout with Russia. For Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies that depend so heavily on oil revenue, the price-war wiped millions of dollars from their projected incomes.

To make things worse, by March it became clear that COVID-19 was not going away but was, in fact, a global pandemic. It would soon cripple entire economies and all but decimate sectors like tourism and high-street retail.

To face this double-barrelled shockwave head-on, Gulf states have taken a number of measures including budget cuts and stimulus plans. These have been coupled with a string of government decisions aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19, in the belief that the sooner the virus is overcome, the sooner economies can start to recover.

With that in mind, Gulf countries have shut their borders, barred residents from entering, and imposed lockdown restrictions that have hit businesses hard.

These unprecedented events have led some analysts to paint a bleak future for what have historically been the region’s most stable economies. But is the outlook for each GCC member the same?

Stimulus packages

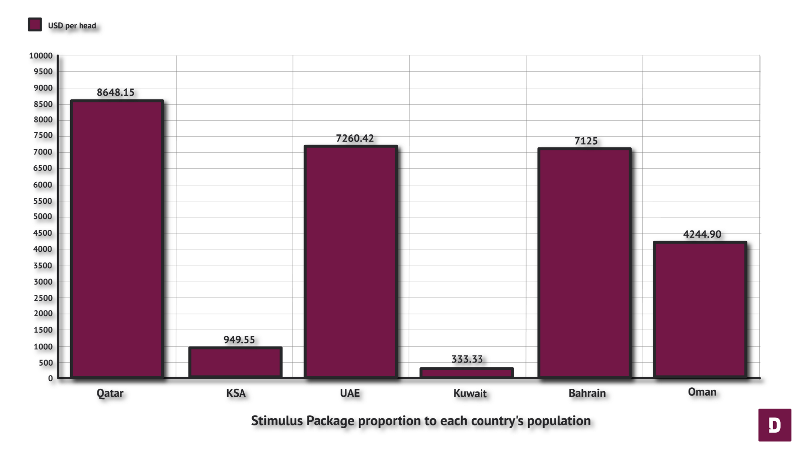

These are basically attempts by governments to use money to restart or stimulate the economy. Large funds are dedicated to different sectors to help offset their losses or boost activity. In the past few months, GCC states have announced stimulus packages amounting to more than 10% of GDP in Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait; over 7% of GDP in Saudi Arabia; and nearly 30% of GDP in Bahrain and Oman according to one report.

Qatar (population 2.7 million) implemented a multifaceted stimulus package of QAR 85bn (US $23.35bn) on 16 March, made up of QAR 75bn for the private sector and an additional QAR 10bn boost into the capital markets on the Qatar Stock Exchange.

Saudi Arabia (population 33.7 million) topped up its stimulus package by SAR 70bn (US $18.6bn) on 20 March, resulting in a combined package of SAR 120bn (US$32bn).

The United Arab Emirates (population 9.6 million) doubled the size of its stimulus package from AED 126.5 bn (US $34bn) since 22 March to currently AED 256 bn (US $69.7bn).

Kuwait (population 4.8 million) has not formally announced the total value of its financial stimulus package. However, the country’s central bank has reduced the discount rate to 1.5% from 2.5%. The state has also announced a KWD 500 million (US$1.6bn) increase to the 2020–21 ministries and government budget.

Bahrain (population 1.6 million) implemented a stimulus package of BHD 4.3bn (US $11.4bn) on 17 March. It will slash spending by ministries and government agencies by 30% to help the country weather the COVID-19 outbreak.

Oman (population 4.9 million) has announced the value of its stimulus package of OMR 8bn (US$20.8bn). The Oman Covid-19 Supreme Committee also implemented a range of incentives to support private sectors firms and workers on 15 April, although the financial value of such measures has not yet been confirmed.

(*All conversions are approximate and were correct at the time of writing.)

Expat job losses

Before we look at how many expats are expected to lose their jobs, let us compare how GCC countries dealt with non-nationals during this pandemic.

Qatar has come under criticism for not allowing residents to return, with thousands still stranded abroad and unable to come back to their jobs, families and homes before August at the earliest. That is in stark contrast to the UAE for example, which has allowed resident visa holders to enter the country since June 1.

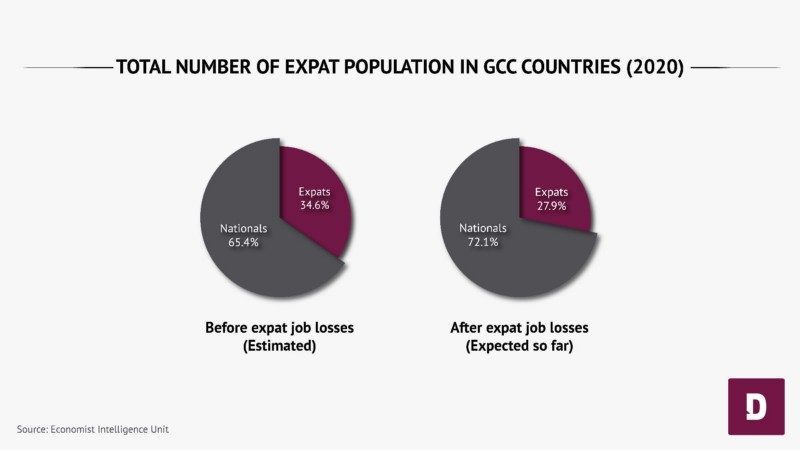

Foreign migrants make up a huge proportion of the Gulf region’s working population and, with the current pandemic affecting economies negatively, many have lost their jobs and had to move back to their home countries.

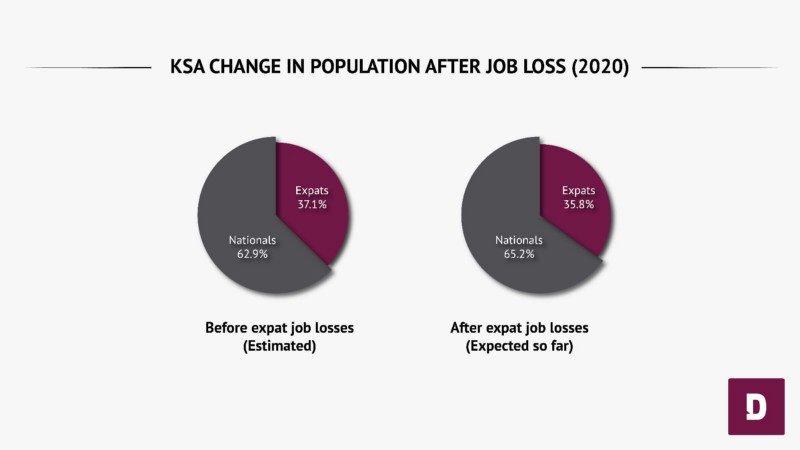

Almost all GCC nations are expected to reduce their expatriate population significantly, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, with up to 10% of foreigners there predicted to lose their jobs.

Qatar however has taken a different approach. Instead of introducing widespread mandatory redundancies, at the start of June, the Ministry of Finance instructed government entities to reduce monthly costs for foreign employees by 30%. This means that foreigners may suffer cuts to their salaries and benefits but won’t necessarily lose their jobs like in neighbouring countries.

Saudi Arabia is expecting to see around 1.2 million expats leave in 2020. Most of these workers are reported to be axed from sectors including accommodation and food services, administration, and support activities.

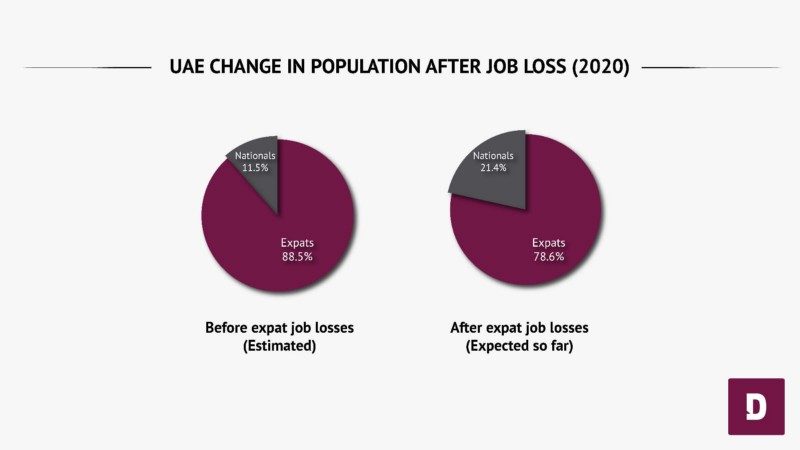

Forecasts indicate that the UAE could lose 900,000 jobs and see 10% of its foreign residents leave the country. Sectors that rely on professionals and their families — such as restaurants, luxury goods, schools and clinics — are expected to suffer as people leave.

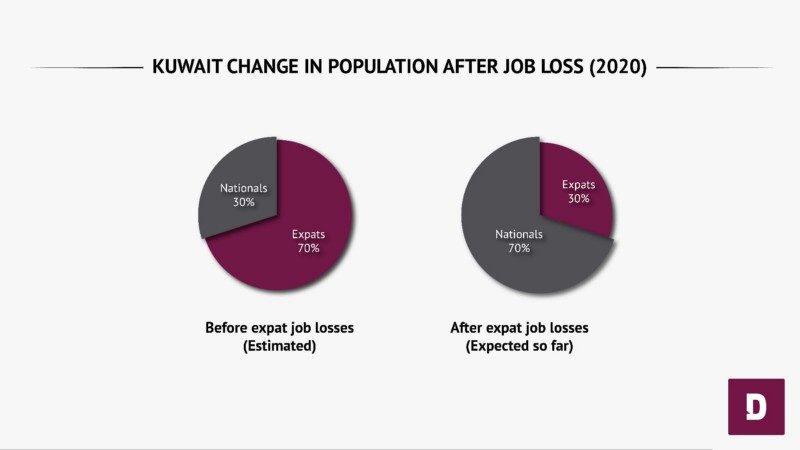

Kuwait recently announced that it needs to drastically bring down the expat population by more than 50%. Foreigners account for nearly 3.4 million of Kuwait’s 4.8 million people, which makes it a bizarre announcement for a struggling economy. Kuwait’s Municipality will soon dismiss all expats, freeze the hiring of foreign nationals, cancel appointments under process and not renew the contracts of existing employees.

Bahrain’s labour market is set to lose over 8,000 workers due to the pandemic. The country also announced that some of its prominent companies, including Bahrain Petroleum, will let go of hundreds of expatriate workers.

Oman has asked all state-owned firms to fire expat workers. While numbers are not specified, expat workers across all sectors of the economy will now likely face job losses and cuts in salary and benefits.

GDP deficit

With the COVID-19 outbreak still largely out of control, experts predict Gulf countries will experience the worst economic crisis in their histories. According to a report by Fitch Ratings, most GCC states are expected to post fiscal deficits of 15%-25% of GDP in 2020.

Qatar’s deficit, which is currently posted at 1.8% of GDP, is predicted to drop to 4.3% by the end of this year when the country is expected to show a fiscal surplus of 5.2%. This means that Qatar will be the only Gulf country not to record a loss in 2020. IMF data has also highlighted Qatar’s real GDP growth to be the highest within the GCC.

Saudi Arabia is set to face a GDP deficit of 15% by the end of this year, spiking from 4.5% in 2019. And according to S&P Global, the UAE is forecast to post a fiscal deficit of 6.3% of GDP in 2020 and 5.1% in 2021.

Kuwait’s fiscal deficit is estimated to worsen from 3% of GDP in the financial year 2018–19 to 13.6% in the financial year 2019–20, driven by higher spending and lower oil revenues.

Bahrain is set to show a fiscal deficit of 15.7% of GDP this year, which is expected to drop to 12% in 2021.

Oman’s deficit could widen to 16.1% this year from 9.4% in 2019 according to IIF. The country’s fiscal and external deficits will remain under immense strain due to low oil and gas prices. Rigid recurrent spending will keep public debt high at an estimated 60% of GDP in 2020, and to increase further in the years to come.

Based on these numbers, it is evident that Qatar fares better than its neighbours when tackling the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. With its GDP deficit far below that of other countries in the region, it has not — so far — had to take any radical steps when it comes to its expatriate workforce.

Whether it’s the countdown to the FIFA 2022 World Cup or a conviction and acknowledgement by officials that the expat workforce is critical for Qatar’s economic success; the government seems to have chosen policies that will safeguard expat jobs as much as possible — at least compared to neighbouring countries. Despite the unprecedented regional and global economic volatility, job security appears to be greater in Qatar than other countries, but many expats will find that hard to appreciate right now when they have loved ones unable to re-enter the country.