Fast fashion is the second largest polluting industry in the world. It produces 10% of the global CO2 emissions, that’s more than airplane and ship traffic combined.

A sense of cognitive dissonance often defines people’s relationship with fast fashion, as they perceive it ‘hypocritical’ to sit in a Zara shirt and read about its harms on the environment and unethical labour practices.

Robert Gifford, a renowned environmental psychologist, describes the phenomena as “the mental discomfort created by holding more than one conflicting belief at once.”

Internal harmony is achieved through aligning one’s thoughts and behaviours, something that doesn’t appear to happen often enough in the world of fashion.

And so, if you’re anxious about climate change and care about labour rights, but don’t necessarily reflect this in your consumer habits. Don’t worry, you’re not alone.

After years of buying shirts that only lasted three-weeks before they became socially unacceptable to wear, and donating or throwing out clothes that you’ve only worn once after being so excited to purchase, you will eventually come to the realisation that: this ain’t it.

Did you know that that one shirt you threw away used 2700 litres of water to be made, which is almost as much water as you’d drink in 2.5 years.

The existence of fast fashion is difficult to reverse, in-fact it has reached its peak in recent years.

Given our rush to keep up with the latest fashion trends, our closets have become overloaded with garment pieces with a three-month fashion-approved lifespan.

What is fast fashion?

From the consumer’s perspective, fast fashion has three primary characteristics: it is cheap, trendy, and disposable.

It makes buying garments in the spur of the moment simple and affordable. To keep up with ever-changing trends, shoppers are encouraged to refresh their wardrobe on a frequent basis throughout the year.

The problem as presented is not with customers who cannot afford the often absurd prices of sustainable fashion and/or cannot thrift, and thus buy few fast fashion pieces; rather it is those who spend $500/month on Shein hauls that will last them half a season.

Labour exploitation

Fast fashion is built on globalisation, and like all exploitative sectors, it is fuelled by low-wage labour that allows for high profits at low manufacturing costs. Its business model thrives on the mass exploitation of individuals who are a part of its supply chains.

The industry’s workers are underpaid, overworked and forced to work in hazardous conditions as a result of low-cost fashion.

Globalisation shifted clothing production from Western Europe and North America to the Global South in the beginning of the 1970s.

Garment workers, who were once direct employees of major brands, have transformed into peripheral players in complex global supply chains. As a result, major fashion brands were no longer required by law to pay fair wages or provide employment benefits.

Garment workers in the Global South have struggled to make ends meet for years due to exploitatively low wages.

It has been almost 10 years since a fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory in Bangladesh killed at least 112 workers in November 2012.

The fire, which was likely started by a short circuit on the ground floor, quickly spread across the nine floors, trapping garment workers due to narrow or blocked fire escapes. Many people died inside the building or whilst attempting to flee through the windows.

Only five months later, the Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing 1,134 garment workers and injuring hundreds more.

Rana Plaza was an eight-story commercial structure with garment factories on the upper floors. The factory management had forced workers to return despite the building having been evacuated the day before, after cracks were discovered.

These two catastrophes, as well as a spate of other disasters in garment factories across South Asia, highlighted the garment industry’s harsh working conditions and the terrible cost of “fast fashion” to employees who create clothing under tight deadlines for extremely low pay. In the years thereafter, a slew of new programmes have been launched to improve industry safety and compensate wounded workers and their families.

The Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, signed by over 200 brands and global unions in 2013, took significant steps toward holding global garment businesses accountable for the safety of facilities in their supply chains.

Building inspections, improvements, and closures if facilities are considered structurally hazardous – are amongst the measures taken in an attempt to hold brands and merchants contractually liable for the safety of the factories where their products are manufactured.

Let’s talk environment

Globally, a truckload of textiles lands on a dumpster every second, or are burnt.

Fast fashion produces 10% of the global CO2 emissions, which more than airplane and ship traffic combined, making it the second largest polluting industry in the world.

Whilst we cancelled straws because we love the turtles and now have to live with the inconvenience of paper straws, 35% of new micro-plastics in the ocean comes from their production.

Plastic straws only make up about 1% of the plastic waste in the sea.

One kilogramme of cotton requires 10,000 litres of water, whilst a cotton shirt requires approximately 3,000 litres.

Textile dyeing also necessitates the use of hazardous chemicals, which end up in our oceans. This process, which accumulates over time, is responsible for an estimated 20% of the wastewater produced worldwide.

Because so many factories have moved overseas, they may be in countries with lax environmental regulations, allowing untreated water to enter the oceans; unfortunately, the resulting wastewater is extremely toxic, and in many cases cannot be treated to be made safe again.

The industry also has an overproduction problem, as up to 30% of products never get sold.

When it comes to reusing their own resources, only 1% of textiles are made out of old fabrics.

Over 3500 chemicals are used in the creation process, 750 of which are harmful to one’s health, whilst 440 directly harm nature.

Shein’s reinvention of fast fashion

The fast-fashion titan has tripled its revenue in three years, hitting $15.7 billion in revenues, and is now seeking $1 billion in capital and a valuation of $100 billion.

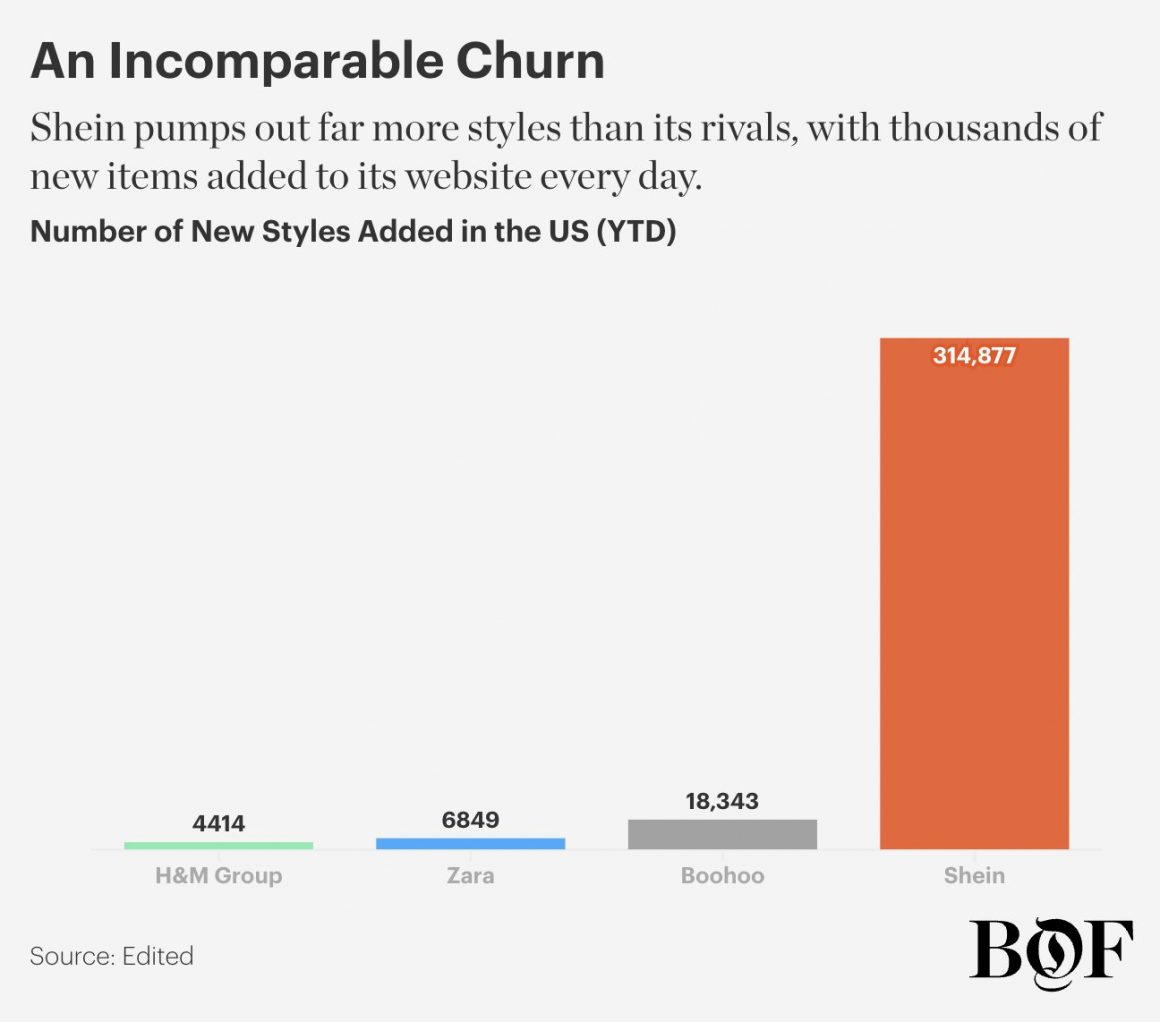

Every day, Shein reportedly adds over 1,000 new outfits on its website. For context, Zara normally has 2,000 products in a 30-day period.

Shein’s forecast presents a dreadful vision of the future of fast fashion, in which we consume clothing for less than $5 USD and buy massive amounts every year.

We’ve grown much more conscious of our consumption as customers, and we have begun to put pressure on some of the world’s largest fashion labels to take responsibility and implement sustainable programmes.

However, there are no sustainability measures or transparency surrounding Shein’s production and manufacturing operations, and despite that, many people continue to buy from the website every day.

Shein’s success is partly owed to its tech-driven approach, according to The Business of Fashion, which uses AI software to import emerging styles from social media and across the internet directly into its manufacturing floor computers.

Change begins small

So, what can we do as environmentally conscious consumers, especially if high-end, “slow fashion” labels are out of an average person’s price range, or if designer stores don’t provide inclusive sizing?

We can try to break our own overconsumption cycles.

That would mean being okay with wearing an outfit more than once. It also means that individuals have to develop a personal style that does not revolve around a constant stream of newness.

It is not poor people keeping fast fashion in business. It is people buying a dozen outfits at a time.

As much as we’d like to place all the blame on corporations, it’s not only them. So much of the core issues with fast fashion is that people want to over-consume. This calls for a mass perspective shift. Instead of acquisition, focus should be on longevity instead.

With this being the start of Doha News’ newly-launched sustainability series, keep an eye out for our next piece discussing how you can be a more sustainable consumer, even if fast fashion is your only option.