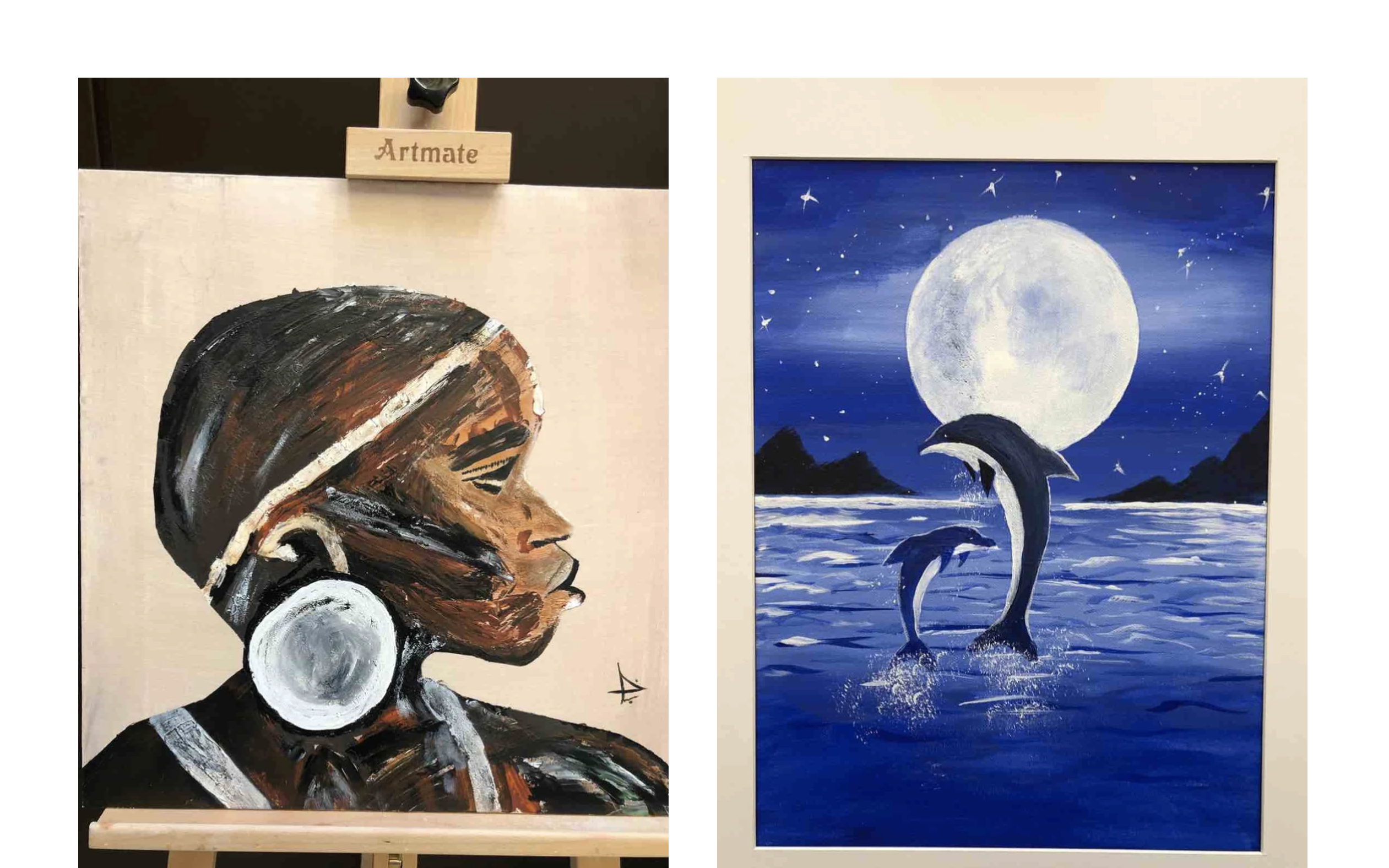

Kirimi has been organising informal sessions with migrant workers to raise awareness on mental health, using art and painting as coping mechanisms.

Eric Kirimi was 23 years old when he first made a deliberate attempt to end his life. At the time, he was working in the Kenyan National Service – the military – and had been battling passive suicidal thoughts for years.

“I was angry. I had nobody in my life. I was in a place where I didnt know who I was. I wanted the pain to end. But something unexpected happened to me right before I did the deed,” the now 29 year old Qatar resident recalls.

“It was not a spiritual realisation or anything like that, I just suddenly had this feeling to try again and give life another chance, including making peace with my past and seeking help.”

Kirimi was living in Kenya at this time, where he was born and raised. Due to a difficult childhood and lack of parental support throughout his adulthood, he struggled without acknowledging that he was mentally unwell because of mental health stigma.

“After that first attempt, I decided to seek help so I went to a week-long retreat,” he recalls. “I also decided to finally speak to my mother to understand why she abandoned me, which gave me some sort of closure to move on and forgive.”

Following this incident, Kirimi moved to Doha to work as a security guard. His past mental health struggles motivated him to launch a programme assisting migrant workers in Qatar to deal with their mental health issues.

The Gulf state has been criticised for its mistreatment of migrant workers since it secured the bid to host the 2022 World Cup, with organisations and reports citing human rights abuses including cases of unpaid labour.

One such report was published by The Guardian in February 2021, headlined, “Revealed: 6,500 migrant workers have died in Qatar as it gears up for World Cup” in which it linked the “shocking” death rate to the start of the World Cup journey a decade ago.

The article has since been disputed however, with Qatari officials slamming what they described as a “misleading” figure that included the overall deaths of all Asian nationals in the country at the time, including many who had not been working on World-Cup related projects.

Authorities also say widespread labour reforms have been unveiled to tackle the concerns, noting such efforts have been widely overlooked by critics.

There currently is no clear data indicating the prevalence of mental health issues among migrant workers in Qatar, but reports have suggested that single male migrant workers, who make up almost 50% of the nation’s population, are at a much higher risk of depression and other mental health issues.

Doha News talked to Kirimi, who has been working on raising awareness about migrant workers’ mental health through art and painting.

Using art to improve migrant mental health in Qatar

Kirimi has been organising informal sessions with some migrant workers to raise awareness on mental health, using art and painting as a coping mechanism.

The young Kenyan himself did not know how to paint until he moved to Doha.

It all started when he had a conversation with the dean of Georgetown University in Qatar, one of Qatar Foundation’s partner universities, upon attending an art exhibition whilst working as a security guard there.

“We talked about my life, and when he asked if I could paint, I wasn’t sure whether to say yes or no since I had never even touched a brush or smelled paint before,” he explained.

“I knew I could draw because I used to draw animations and comics as a kid. When he asked, I knew it was something I wanted to try in the future, so I told him, “Yes, I can paint,” and a result, he asked me to paint something for him.”

The following week, Kirimi spent nights watching youtube tutorial videos. He created his first painting, which the GU-Q dean then appreciated and encouraged him to paint more for an exhibition. Over the following few weeks, Kirimi’s work was displayed in exhibitions at Qatar Foundation and was gaining ample attention.

In addition to making extra cash, the younger painter realised that he could do so much more with art to raise awareness about causes he cares about; this is when he founded Doha-Run Educational Art Mission (D.R.E.A.M), a programme he is still working on implementing to support other workers.

“Migrant workers here have amazing stories to tell, which are not just limited to the daily struggles they face,” Kirimi told Doha News, stressing that this project intends to fill the gaps within the system by providing a space for migrant workers to explore their creative potential, which is often underestimated.

Kirimi has been organising workshops with migrant workers and holding art therapy sessions in the Industrial Area for the past two years.

Some of the people he has worked with are migrant workers who have been interested in art since they were children, but were forced to seek other jobs in adulthood and upon arriving to Qatar. Others attend to learn how to paint as a hobby.

Up to 800,000 Asian and African workers, mainly employed as construction workers and security guards, live in the isolated Industrial Area and nearby Labour City, which has been criticised for appearing to segregate Qatar’s migrant worker population from the rest of the community.

The Industrial Area’s popular facilities for migrant workers include a 13,000-seat floodlit cricket stadium, mosques, cinemas and amphitheater with the capacity of 16,000.

According to Kirimi however, there are still not enough recreational spaces for migrant workers from various backgrounds to socialise and exchange stories.

“There is currently one gym here for all of us, so if you can’t go to the gym, or if you are not interested in sports, it would be nice to have a space to unwind and talk to others, which is why having an art centre here would be helpful,” said Kirimi, who still struggles to this day to find a designated space to conduct the art therapy sessions.

Since Kirimi is not an expert in therapy, he has collaborated with two independent volunteer therapists and a professor at Virginia CommonWealth University Qatar, who have been guiding and mentoring him along the way. They provide advice on how to initiate conversations about mental health during art sessions, which can sometimes be challenging.

The painter and security guard is still looking for funding, having had pitched his idea to Qatar’s International Labour Organisation (ILO), Qatar Foundation and other parties. He hopes to find parties willing to invest in migrant workers’ mental health and turn his ongoing informal programme into an actual recreational art centre with the necessary facilities.

“We need art supplies, a venue at the industrial area to hold our workshops, a venue to showcase our works in exhibitions, transportation, licences to display and showcase our work publicly and a variety of other things to make this work,” he told Doha News.

Despite COVID-19 slowing down his progress, Kirimi still tries to find time to reach out to some migrant workers for the sessions, using money out of his pocket to cover needed art supplies.

“A lot of men especially don’t want to talk about how they feel. I have worked with men who miss their families back home. Men who have been here for four years without going home. Some who are struggling with suicidal thoughts due to stress and other issues,” Kirimi told Doha News, adding that this initiative allows migrant workers to talk about their experiences and shared struggles without judgement or fear.

“Sometimes we just need to be able to share our stories and how we feel, either the good ones or the bad ones. Sometimes all a person needs is to be heard. It doesn’t have to be verbal, which is where art comes in,” he added.

Qatar migrant healthcare reforms

While significant progress has been made in improving overall national levels of healthcare in Qatar, access to the system remains a challenge for single male migrant workers in lower-skill positions.

There are various challenges migrant workers face when seeking mental healthcare, including general mental health stigma and the fact that undergoing compulsory medical tests even before before coming to Qatar causes migrant workers, from very early stages of the migration process, to become cautious about revealing information regarding their health, according to a 2019 report by WISH and Qatar Foundation.

“From the pre-departure stage, migrants come to associate their ‘good health’ with being given permission to legally live and work in the GCC. The process that screens out potential migrants on the basis of health concerns leads to many lower-income migrants associating being healthy as a core prerequisite for being in the Gulf in the first place”, the report read.

In order to address some of these challenges, the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy (SC) collaboration with Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS) launched the comprehensive medical screening (CMS) programme in 2018 to give workers a thorough physical examination that includes a mental health assessment.

More than 42,600 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 employees have undergone this health screening programme, according to a recent report.

“These screenings ensure that workers are fit to work before being mobilised on site, that they are well-suited for their tasks and that they receive appropriate care plans in case of any medical issues,” stated the report.

This programme aims to identify underlying health issues at an early stage so that workers can receive effective medical care and maintain optimal health.

Using art to cope with mental health specifically has also been helpful to Kirimi as an individual, in addition to supporting his colleagues.

“Art and painting has a way of lighting up the brain to positivity and self confidence,” he said.

“Everyone can be an artist and I was lucky enough to realise this. I want to share how it impacted me mentally so that my colleagues can also benefit.”