Photos by Peter Kovessy

Roughly 35km west of Doha, Cromwell Purchase is bringing one of the rarest birds on earth back from the brink of extinction.

The South African native is the acting director and head of birds at the Al Wabra Wildlife Center, owned and run by Sheikh Saoud bin Mohammad bin Ali Al Thani, which is home to roughly three-quarters of the world’s 90 or so Spix’s macaw.

The blue parrot – popularized in the 2011 movie Rio – is indigenous to northeast Brazil, but hasn’t been spotted in the wild since 2000.

Purchase and his colleagues at the center are breeding the birds, researching new reproduction strategies and preparing to reintroduce the Spix’s macaw back into its natural habitat in Brazil.

“Just looking after birds in a cage is not conservation,” Purchase told us as he gave Doha News a tour of the 2.5 sq km facility last week.

Fighting the odds

The Spix’s macaw is what Purchase calls a “niche” bird. It was already a rare species when it was first discovered in 1819.

Livestock – namely goats – were decimating the bushes producing the fruits and nuts that accounted for much of the birds’ diets. Inherently low fertility levels among males and females were limiting their reproductive success, and the Spix’s macaw was not evolving and adapting to climate and habitat changes as fast as other parrots.

“They were busy getting extinct on their own,” Purchase says.

Meanwhile, logging was destroying their nesting grounds, while poachers raided the remaining nests for young birds to sell to private collectors of rare species.

“This created a crisis for a species already on the brink,” Purchase added.

Given the multitude of challenges facing the species, Purchase admits he’s been asked why he’s focusing his work on a bird facing odds that he concedes “are very much against them.”

Part of the answer is that in trying to preserve the Spix’s macaw, Purchase and his team are advancing research in areas such as artificial insemination that will benefit other species facing extinction in the future.

But Purchase says there’s a bigger reason:

“We’ve got a person (who’s) interested in saving a species and has the money to do it.”

Al Wabra

Sheikh Saoud bin Mohammad bin Ali Al Thani inherited a hobby farm outside Ash-Shahaniyah from his father and began hiring scientific staff to turn it into the Al Wabra Wildlife Center in 1998-99.

The center is not open to the public, but is expanding its outreach efforts and has started working with local schools. It employs some 200 staff, including 50 animal professionals.

It currently has some 2,100 animals belonging to 90 species, including antelopes, sand cats and various birds of paradise. This makes it unlike a zoo, which typically strives to give guests variety by having a wide range of species, but only a few of each kind.

Not all the creatures at Al Wabra are rare. Researchers hope that by working with species similar to those that are endangered, they can develop successful strategies in creating artificial habitats, for example, to help them look after threatened animals better.

Spix’s macaw in Qatar

Purchase says Al Thani learned of Spix’s macaw recovery programs in Switzerland and the Philippines that were in trouble, and bought their collections in 2002-04.

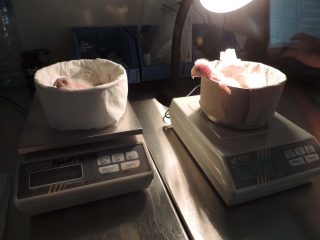

Slowly, the center’s Spix’s macaw population increased. Five chicks were born in 2012, with another seven – two from artificial insemination – hatched last year.

With the 2014 breeding season still underway, five new birds have so far been added this year to Al Wabra’s population.

Later this year, construction will commence on a dozen new breeding enclosures. Unlike the existing 26, the new structures will have common “flocking” areas allowing the birds to pick their own mates.

This is significant, Purchase says, because Spix’s macaws that choose their own partner generally start reproducing between the ages of three and four, compared to standard seven to nine years of age for most in captivity.

One of the biggest challenges Purchase faces is the lack of genetic diversity within the remaining Spix’s macaw population. That makes the advances in artificial insemination so critical, as it allows researchers to breed different combinations of males and females to create the best possible genetic combinations.

Purchase says he hopes to one day be able to extract the DNA from preserved Spix’s macaw on display in museums – his own Jurassic Park moment – to increase the diversity of the living population.

Back to Brazil

Back in Brazil, the center owns some 2,800 hectares of land outside the town of Curaçá in the northeast that’s been fenced off and recently designated a protected area by that country’s government.

Purchase says he hopes the habitat will have sufficiently regrown and that the captive birds’ genetics adequately strengthened to reintroduce the Spix’s macaw into the wild in 2019 – coinciding with the bicentennial anniversary of the species’ discovery.

In preparation, the center has funded a school in the region as well as a “cultural caravan” that educates the local population on sustainable farming methods as well as the benefits – such as increased tourism – of protected the endangered birds when they are released.

“We need the community on board for this to be a success,” Purchase says.

Thoughts?